Viking Age (750 – 1100 AD)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

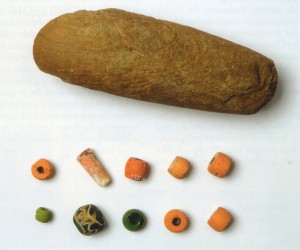

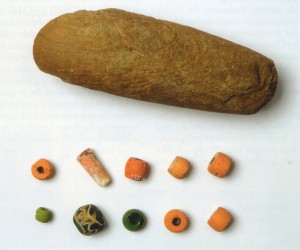

SUPERSTITIOUS VIKINGS. In 2006 we found a female Viking burial at Kongshaugen (King’s Hill), Avaldsnes. Among the burial gifts were some glass pearls and a thunderstones, a Stone Age axe, to protect her from evil forces. (Photo AmS)

See “The Thunderstone Mystery”

THE ROYAL SEAT AT AVALDSNES

Avaldsnes is referred to as Norway’s oldest royal seat because Harald Fairhair established his main court here after the battle of Hafrsfjord in about 870. But by the time Harald Fairhair settled at Avaldsnes, the place had in reality been a royal seat for sea-kings ever since the latter part of the Roman era.

Some of these kings are only known about through archaeological discoveries, while others are mentioned in written sources like old heroic sagas and Norse poems and in the Icelandic book of Landnáma. We know these kings by name, even though their genealogy is not always to be relied upon and several generations may have been omitted from their family trees.

THE VIKING KINGS BEFORE THE TIME OF HARALD FAIRHAIR

As we enter the Age of the Vikings around 750, the king at Avaldsnes was probably named Hjorleif/Hjørleiv nicknamed the woman-lover. Hjorleif is followed by his son Halv/Half who has his own saga entitled “The Saga of Half & His Heroes“. His name comes from Old Norse há-alfr meaning “the high elf”. In old, written sources we can trace the names of some of Halv’s descendants as follows: Halv had a son called Hjor/Hjør,

This King Hjør sailed a long way northwards, right up to Bjarmland, where he married the Bjarmland princess Ljufvina, who was of Mongolian stock. He brought her back to Avaldsnes and so it was that a Mongolian princess became queen at Avaldsnes.

Hjør and Ljufvina had twins: Geirmund and Håmund, both of who were nicknamed “Hejlarskinn”, which means “dark-skinned”.

Hjør and Ljufvina probably reigned at Avaldsnes around 870, when Harald Fairhair settled there. We do not know what happened to the old king and queen, but their son Geirmund Heljarskinn went on Viking raids to the west at this time and accumulated great riches in Ireland. He then went to Iceland and we learn in the book of Landnáma that he was called “the greatest of all the men who had taken lands in Iceland”.

The image shows the “workshop area”, the “living area” and the area for religious/political activities in those locations that have been investigated. (Photo KIB Media)

THE ROYAL COURT(S) AT AVALDSNES

Over the centuries, a number of royal courts have existed at Avaldsnes, each of which had many buildings for different purposes. In the areas studied by the Royal Manor Project in 2011 and 2012, traces of several of these royal courts were found.

In addition, traces of settlements dating from the early, middle and last part of the Viking Age were discovered. Roughly speaking, throughout the whole of the Iron Age, including the Viking Age, the “workshop area” lay east of the existing outbuilding. The “living area” lay on a flat piece of land between the existing outbuilding and the church. The hall, used for religious and political activities, was situated on the edge of this flat land, just south of the church.

One should, however, remember that only a tiny part of the royal manor area has been excavated. Some buildings have been situated in the areas not yet uncovered, others have been destroyed through the centuries. Thus; we can only get a hint of what the royal courts have looked like.

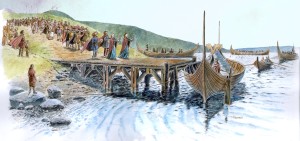

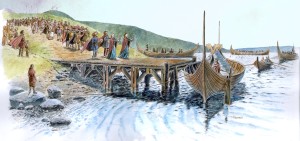

THE ROYAL COURT’S HARBOUR

It was its strategic position on the strait of Karmsundet that made the royal court at Avaldsnes so important to the old kings, as they gradually unified Norway into one kingdom. While they resided at Avaldsnes, the kings could control all traffic along the coast. They could collect taxes and control enemy ships and Avaldsnes was also the perfect starting point when ships were sent over the sea on Viking raids or trade missions. The resources of the royal courts also meant that there was room for many warriors.

There are many places near the royal court that make good harbours. We know that the entire royal war fleet was anchored at Avaldsnes for some periods of time and every nook and cranny must have been filled with ships at these times. In general, we assume that the kings of the Viking era used the same harbours as the medieval kings: from the stretch of coast just below the Nordvegen History Centre to the area south of Bukkøy. Along this stretch, we find many traces of maritime activity.

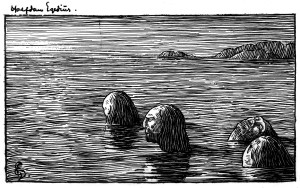

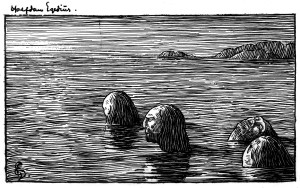

“The sourcerers at Skrattaskjær”.

(Ill. H. Egedius in Saga of Olav Tryggvason)

DRAMATIC EVENTS AT AVALDSNES

From the time of Harald Fairhair onwards, Avaldsnes’ history is closely linked to the history of the Norwegian national kings. In the royal sagas, we can read about several dramatic events at the royal court:

OLAV TRYGGVASON AND ODIN

Snorri relates that Olav Tryggvason once received a visit from an old, one-eyed man who told him the story of King Augvald, the king from the Age of Migration who gave his name to Avaldsnes. Following their conversation, King Olav had difficulty in sleeping and therefore got out of bed in order to look for the old man. When he went down and spoke to the cook, he was told that the one-eyed man had tried to poison the king’s food. Olav Tryggvason then realised that it was Odin himself who had visited him.

OLAV TRYGGVASON AND THE SORCERERS (“SEID MEN”)

On another occasion, at Easter in 998, a ship full of magicians and sorcerers arrived at Avaldsnes. Their leader was Øyvind Kjelda and they came to cast a spell over the king because he had brought Christianity to the country. The sorcerers conjured up a thick, black fog, but the fog turned in the direction of the sorcerers themselves, causing them to stumble around in confusion. The king intervened and tied the sorcerers to a rock and when the tide came in, the sorcerers drowned. Since then, the rock has born the name of Skrattaskjær (“Sorcerers’ Rock”).

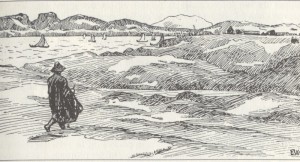

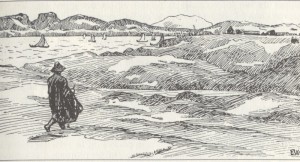

Asbjørn Selsbane on his way to the Royal Residence at Avaldsnes. (Saga of St. Olaf. Ill. E. Werenskiold)

ST. OLAF AND ERLING SKJALGSSON

Olaf the Holy also experienced a dramatic event at Avaldsnes. It was Easter in the year 1023 and Olaf had just sentenced Asbjørn Sigurdson of Trondenes to death because Asbjørn had brazenly decapitated the king’s steward, Tore Sel.

While the king was attending a service in church, a message was sent to Erling Skjalgsson, telling him what was about to happen. At this time, Avaldsnes was a bastion of the king in the West, but the person wielding real power was Erling Skjalgsson, who was Asbjørn Sigurdson’s uncle. Erling arrived at Avaldsnes with 1500 men to save his nephew. Olaf had no choice but to pardon the murderer, who was later named Asbjørn Selbane.

This event at Avaldsnes caused bad blood between the clans and resulted in the battle at Stiklestad, where another of Asbjørn’s uncles, Tore Hund, killed Olaf the Holy.

Penannular brooch from Blood Heights, 900’s. (Photo AmS)

THE BATTLE OF BLOOD HEIGHTS

In 953, a Danish/Norwegian army led by Eirik Bloodaxe’s sons sailed up the strait of Karmsundet. They landed at Avaldsnes where they fought a bloody battle against their uncle Håkon the Good amongst the Bronze Age mounds at Blood Heights. The chronicler Agrip relates that three of Eirik Bloodaxe’s sons died in this battle, but Snorri only mentions Guttorm Eiriksson.

SHIP BURIALS BY KARMSUNDET

Two of the 14 known burial mounds containing ships in Europe, Storhaug (The Great Mound) and Grønhaug (The Green Mound), are situated in Avaldsnes.

Dendrochronological (tree-ring) studies from 2009 show that the Oseberg ship was also built in this area. See:

Arkeologi i nord: Osebergskipet fra Sørvestlandet

Academia: From Avaldsnes to Oseberg: Dendrochronology and the ship graves from Karmøy, Rogaland.

Between Sutton Hoo and Oseberg – dendrochronology and the origins of the ship burial tradition

Storhaug and Grønhaug were opened in 1886 and 1902 respectively. Grønhaug had been raided by grave robbers shortly after the mound had been completed, while Storhaug had fallen prey to farmers hungry for soil in more recent times. Nevertheless, the contents of the mounds still remaining showed that these ships had been equally as richly equipped as their better-known counterparts Oseberg and Gokstad. This was taken as a sign that Harald Fairhair had brought the Yngling clan’s burial customs with him when he settled at Avaldsnes. The archaeologist Haakon Shetelig even hinted that Harald Fairhair himself could be buried in one of these mounds.

Two large neck rings of silver, Viking Age, found by the seaside, North Eike. Possibly granted as a token of alliance to persons who performed important duties for the king. (Photo M. S Vea)

New research based on sources older than Snorri leads us to reject the theory that Harald Fairhair came from the Yngling clan. Rather, he is believed to be a king of Western Norway. His mother came from Sogn and he lived for the most part in the South West. It has also been confirmed that both the ships from Storhaug and Grønhaug are older than the Yngling clan’s burial ships in Vestfold.

GRØNHAUG SHIPBURIAL (790-795)

Grønhaug (Green Mound) lies on the outskirts of Blood Heights, where according to Snorri, the battle between Håkon the Good and the sons of Eirik Bloodaxe took place. The mound was about 30m in diameter and 4m high and contained a ship that was 15m long and 3m wide on which a chieftain was laid out on duvets of down. Studies of his bones have revealed that he was once a large, strong man.

The burial mound had obviously been disturbed by grave robbers, but the remaining objects, such as tapestries and English glass, indicate that it must have been full of riches. In 1998, the Grønhaug ship was dated at ca. 930 AD. C-14 tests were carried out on large pieces of good-quality birchbark and the subsequent dating led researchers to believe that this could have been Harald Farhair’s grave.

Snorri writes that Harald was buried “heygðr á Haugum við Karmtsund” which probably means that he was buried in a mound at place called Hauge by the Karmsund, and Grønhaug is indeed located just near Haugo Farm at Torvastad. Grønhaug was also mentioned as a possible burial ground for Harald Fairhair’s grandson Guttorm Eirikson – one of the men who fought against Håkon the Good at the battle of Blood Heights at Avaldsnes in ca. 953.

The location of the ship burials Grønhaug and Storhaug in relation to the Royal Residence at Avaldsnes. (Photo KIB media)

In 2009, dendrochronological (tree-ring) dating of the ship’s timber was carried out, which showed that the trees used to build the ship were cut down in ca. 780. The burial itself took place between 790-795.

These datings from different periods may indicate that several burials were carried out in this one mound. If Harald Fairhair or Guttorm Eiriksson were buried at Grønhaug, they must then have been buried in a grave mound that already existed.

RITUALISTIC GRAVE DESECRATION SHORTLY AFTER BURIAL

Grønhaug was desecrated a very long time ago. The location of the mound, clearly visible from the royal court at Avaldsnes, means that nobody could break into the mound and rob it undetected. Furthermore, it looked as though somebody had tried to drag the dead body out of the mound, as only parts of the skeleton were found. So what was the motive for this break-in?

At Jellinge in Denmark, we know that Harald Bluetooth took his parents Gorm and Tyra out of their mounds and buried them in Jellinge Church. Perhaps somebody wanted to do the same thing with the dead man at Grønhaug, thereby “Christianising” him post mortem? Or was it a new dynasty which entered the burial mound in order to consolidate its power over the pagan rulers of the past? A wax candle was found in Grønhaug – a clear mark of Christianity. The sagas, too, relate that wax candles were used to render the dead harmless when graves were entered – a practice that was carried out in order to prevent haunting.

The chronicler Odd Munk tells a unique story about Olav Tryggvason’s digging in King Augvald’s grave mound at Avaldsnes. While the king was living at Avaldsnes, he was visited by Odin in disguise who told him about the mounds where Augvald and his sacred cow lay buried. Olav Tryggvason found human bones in one of the mounds and bones from a cow in the other.

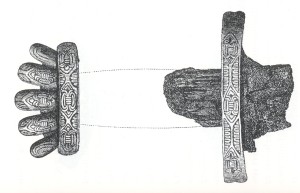

According to the sagas Olav Tryggvasson opened several burial mounds at Avaldsnes. Was he the one who opened Grønhaug in the 10th century? (Illustration Dag Frognes)

STORHAUG SHIP BURIAL (779)

The other burial mound containing a ship, Storhaug (Great Mound) at Gunnarshaug is located a little further north of the royal court. Before farmers began to remove earth from the mound, it was between 40 – 50m in diameter and 5 – 6m high. Its position on a flat piece of ground at the narrowest part of the strait of Karmsundet, must have made it appear even higher.

The farmers’ digging had uncovered different objects made of iron, from this only a spears and a bunch of 24 iron arrows, rusted together in a quiver, have survived. The excavation of the grave was carried out at great speed and findings from as late as the 1970s reveal that there are even more remains in the mound. Nevertheless, we still know quite a lot about the King of Storhaug and his ship.

When Storhaug was opened in 1886, the King still had two swords and two spearw, a fire steel and a bronze ring, pliers, files and other tools for fishing and cooking. He had also been buried with a beautiful gold arm ring and two sets of costly board games, one with counters made of amber and the other with counters of blue and yellow glass. In addition, the prince had a smaller boat and a horse. Interestingly, the Christian symbol of a cross pricked into the surface of a candle was also found in Storhaug

The keel of the ship was about 22m and the ship itself must therefore have been at least 27m long. The remains of the ship from Storhaug contain important information about details of shipbuilding which only this mound has been able to provide. No traces of the mast or mast fish were found, which may be due to earlier damage. An alternative explanation is that this was a large rowing boat, a kind of “missing link” between the rowing ships and the full-blown sailing ships.

Arm ring of gold found in Storhaug. Bracelets of gold is regarded as insignias. This is the only arm ring of gold found in a burial mound in Norway from this period.. (Photo Bergen Museum)

Dendrochronological dating conducted in 2009 revealed that the Storhaug ship was built in the year 771 and buried in 779 AD. Though the King is buried on a Nordic ship, his equipment is that of a Frankish aristocrat. His sword, for example, resembles a type made in the region around Aachen, Charles the Great’s imperial capital.

Storhaug, Norway’s oldest known burial ship, bears signs of Christian influence about 200 years before Christianity was introduced in Norway. The grave gives us a clear indication that a powerful dynasty with international contacts lived at Avaldsnes during the centuries before unification. It also shows that as early as the late 8th century, the beginnings of a state began to emerge at Avaldsnes which later led to the unification of Norway.

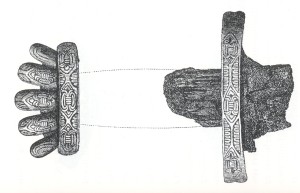

SHIP’S BOWS FOUND ON A FARM, HAUGESUND

In their book The Viking Ships, Their ancestry and evolution (1950), Shetelig and Brøgger write that in Stavanger Museum there are “… three unfinished boat bows made of oak and found in a marsh on Gard farm in Skåre.” The director of Karmsund Cultural History Museum, N. H. Tuastad, writes about this find: “30 years ago, materials belonging to the bow and keel of a large boat were found on Gard farm. They had been sunk into marshy water and were left lying there. They are now housed in the museum in Haugesund. Ocean-going boats were built here and were used as such. We can be sure that the shipping lane was the main fairway for people here, from the earliest times…”

KARMØY AND HAUGESUND

In Viking times, there were no municipal borders and in historical terms, North Karmøy Island and Haugesund must be seen as one unit. The ancient borders between farms ran right across the strait and yet today we find names such as Storasund and Litlasund on both sides of Karmsundet.

Sword from Rossabø in Haugesund testifies contact with England in 900s.

North Karmøy and Haugesund are one of the areas in Norway (if not the only area) having the greatest concentration of properties belonging to the crown, and later to the church. There were few farmers here who owned their own land – the monarchy controlled most of the properties.

THE STONE CROSS AT GARD IN HAUGESUND

At Gard in Haugesund there stands a stone cross. We know that other stone crosses stood along the strait of Karmsundet, for example at Storasund, on the island of Karmøy.

Stone crosses were erected in the West of Norway between 950-1050. The county of Rogaland and the southern part of the county of Hordaland are the two regions outside England where most stone crosses from early Christian times are to be found. All these crosses are clearly visible and stand facing the shipping lane. Their presence is clear evidence of influence from the British Isles.

The stone cross at Gard, Haugesund. One of the crosses that appears to be the mark of an early, Christian royal officialdom. (Photo Cathrine Glette)

These large, freestanding stone crosses demarcate the core area of the Gulating legislative region stretching across the present-day counties of Rogaland, Hordaland and Sogn and Fjordane. None are to be found in the counties of Agder further east or Sunnmøre further north. The stone cross at Gard, together with one cross at Kvitsøy and three crosses in Sogn and Fjordane are all hewn from Hyllestad stone. All these crosses are between 2.49 – 3.90m tall. Professor Knut Helle believes that these stone crosses appear to be the mark of an early, Christian royal officialdom. Both determination and organisational ability are required in order to transport large stone crosses of this kind over such long distances.

AVALDSNES AND THE WEST SIDE OF KARMØY ISLAND

There are many findings dating from up until the end of the 8th century in the area of Ferkingstad onnthe west side of Karmøy. It is believed that the chieftains at Ferkingstad were allies of the kings at Avaldsnes. But at the advent of the Viking Age, Åkra, appears on the historic arena. From this period onwards, there are few findings at Ferkingstad and Åkra played the leading role on the west side of Karmøy. This is probably to do with political events at Karmsundet. Perhaps there was a struggle for power at Avaldsnes, when the chieftain of Ferkingstad was on the losing side, while Åkra chose the “winning” side.

This may have led to the farmer who owned large holdings at Åkra receiving privileges at the expense of Ferkingstad. Åkra becomes a chiefdom allied to the kings at Avaldsnes. This is also reflected in property rights: the large farm at Åkra is from this time onwards a freeholding, firstly for chieftains and later for farmers. On other parts of Karmøy Island, we find a large concentration of properties which were owned by the church throughout the Middle Ages.

THE BOAT BURIALS IN ÅKRA

Åkra lies on the west side of Karmøy Island. Three boat graves have been found here. These are more modest versions of the burial ships in Storhaug (The Great Mound) and Grønhaug (The Green Mound) at Karmsundet. However, it is clear that three boat graves of this kind so close together must have had some special significance. A salient feature of the boat graves at Åkra is that they are situated on top of natural mounds which already looked like burial mounds. An enlargement of the natural mounds must have been an extremely monumental focal point in the otherwise flat landscape at Åkra. The burial mounds are easily visible from the land and from the sea.

Sword found at Åkra. Testifies contact with England in 900’s. Same type as the Gillingsverdet. (Photo AmS)

Boat graves and the sea are often linked to “vaner” or fertility gods. The best known of these gods were Njord, Frøy and Frøya. In one of the boat graves at Åkra, a woman was found. Perhaps she was Frøya’s priestess? The sacrificed dog and horse in her grave evoke associations to a fertility cult. The same applies to the location of the boat grave at Åkra (which means “sacred field”). Apart from being a goddess of fertility, Frøya was also a Valkyrie and as such, would coming riding onto battlefield in a chariot pulled by cats. Here, she picked out half of the fallen men and took them home with her to Folkvang. The other half, whom she did not want, were taken by Odin back to Valhalla.

UNIFICATION OF NORWAY

The machinery of power of which we can see the beginnings at Storhaug was exploited by Harald Fairhair when he began to unify Norway, commencing with the regions of North Rogaland and Sunnhordland. The strong seat of power at Avaldsnes, with its many contacts along the Norwegian coast and over the North Sea, created the political and economic conditions which resulted in the foundations of unification being laid in this area during the Viking Age. What is more uncertain is whether Harald Fairhair came to Avaldsnes as a conqueror or whether he already had allodial right to this area of the land.

HARALD FAIRHAIR’S FUNERAL PROCESSION LEAVES AVALDSNES.

Harald Fairhair dies at Avaldsnes. The sagas tell that he is buried …at Hauge by Karmsund”. (Ill. Dag Frognes)

According to Snorri, Harald Fairhair originally came from Vestfold, a region lying on the west side of the Oslo Fjord. Historians such as Claus Kragh and Knut Helle have presented a new interpretation of sources mentioning the Yngling clan and Harald Fairhair, claiming that Harald’s purported origins in Vestfold was a politically motivated story in order to legitimise the king’s “allodial rights” to the region around Oslo Fjord. Kragh and Helle, on the other hand, believe he was originally a king in the West of Norway, either from Sogn, Kvinnherad in Sunnhordland or from Avaldsnes in Rogaland. Harald’s mother was Ragnhild, daughter of the local king Harald Goldbeard in Sogn, but where did Harald’s father come from?

All Harald Fairhair’s royal courts were situated in the counties of Rogaland or Hordaland. Other parts of the country were ruled by earls on Harald’s behalf and since the Southwest was Harald’s main area of power, it seems probable that his family roots were also in Rogaland and Hordaland.

UNIFICATION AND CHRISTIANISATION

The unification of Norway began in the Age of the Vikings and this was also the age when Norway was Christianised. Contact with other nations was important for the establishment of the new Norwegian state and through their travels, the Vikings were exposed to Christian influences, which also played a significant role in the unification of the country. Marks of Christianity in Viking graves from as far back as before Harald Fairhair’s time bear witness to Christian influences even before the church established itself in Norway. In this way, unification and Christianisation were in many ways two sides of the same coin.

IMPORTANT FINDINGS FROM 900’S IN KARMØY AND HAUGESUND

Important findings from the 900’s in Karmøy and Haugesund. After Arnfrid Opedal) (Ill Steinar Iversen)

Findings from 700 – 1000 century AD. from Karmøy – Haugesund. After Arnfrid Opedal. 2010, (Ill. Steinar Iversen)

Back