Medieval times (1100 – 1537 AD)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

Approx. 25 m of the royal building is uncovered outside the cemetary, but it continues towards St Olaf’s church. The main building is 51 m long, included the tower. (Photo Marit Synnøve Vea)

After Sigurd Jorsalfar’s death in 1130, there was rivalry between different clans and pretenders to the throne. Avaldsnes was a bastion for the Birchlegs (supporters of King Sverre) until 1205. In 1207, we learn that their enemies, the Baglers, had taken control of Western Norway as far as the Bokna Fjord, south of the island of Karmøy, and that the Birchlegs’ prince Håkon Håkonsson was under their power.

13TH CENTURY. NORWAY’S GOLDEN AGE

After Håkon Håkonsson was taken to king in 1217, only 13 years old, the civil war ended. During Håkons reign, Norway reaches its Golden Age. Håkon expanded Norwegian territory to it’s greatest extent. Literature and the arts flourished and Håkon was highly respected by other European rulers. He was also offered the Imperial Crown by the Pope.

Håkon Håkonsson carried out many construction works, and he was the king that started the construction of the fortified royal manor at Avaldsnes around 1250. The Church of St. Olaf, which still stands, was built as an integral part of this royal manor complex

Prof. Dagfinn Skre inside the gate tower. The nicely curved stones at the bottom of the doorway are similar to those in St. Olaf’s church. This may indicate that Håkon Håkonsson built the tower at the same time as he built the church (Photo Marit S. Vea)

A papal decree of 1247 states that King Håkon Håkonsson shall have the right to appoint priests for the churches he and his forefathers had built at the three royal courts and also for those churches he would found in the future. In contrast, at all other churches, priests were appointed by the bishops

THE MEDIEVAL ROYAL MANOR EXCAVATED IN 2017

In 2012, archaeologists made the surprise discovery of a medieval royal manor at Avaldsnes. The ruin was found on the plateau just south of St Olaf’s Church. This is the fourth royal manor built in stone that is found in Norway. The others are situated in Bergen, Oslo and Tønsberg.

The discovery of this fortified royal manor means that we must upgrade the role Avaldsnes played for the royal power in the Midieval period. We must also upgrade the king’s ambitions to build a state administration.

The Avaldsnes Royal Manor project, lead by the University in Oslo, excavated the ruins from June to October 2017. The excavations show that it is the main building of the medieval royal residence that has been found.

Approx. 25 m of the building is uncovered outside the cemetery, but it continues towards the St. Olaf’s church where strong walls of a fortified tower has been uncovered inside the cemetery.

The building had three floors built in stone, included the cellar. The cellar was used as a storage room, probably to store goods received from both taxation and trade. Trade was important, and we know that the royal estate owned a ship called Avaldsnesbussen that sailed to England and traded on behalf of the king.

On the second floor, there were kitchens, workshops and working rooms. On the third floor was the representative hall and other rooms used by the king when he was at Avaldsnes. The building ends in a fortified tower.

Avaldsnes Royal Manor seen from the strait Karmsund. Reconstruction based on archaeological excavations in 2017. (ARKIKON, Ragnar Børsheim)

In addition to host royal residence and administration, the main building had defence features. The tower was 2 m wider than the building itself. That made the defenders able to shoot attackers who managed to reach the walls. It is possible that the church’s high west tower also originally had loopholes for use against attackers. From the tower a covered passageway in two floors, leads up to the chancel.

The façade from the south to the church is 70 m. The main building, including the tower, is about 51 meters.

Håkon Håkonsson, who built the Church of St. Olaf, started to build the royal manor around 1250. Håkon V Magnusson completed the building around 1300.

Ten royal letters written at Avaldsnes have survived. Perhaps they were written in this very hall?

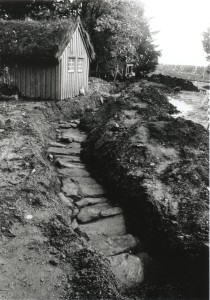

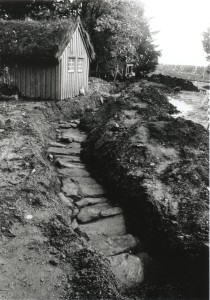

The secret passageway. An escape route to use in times of war and danger. In the gravel you see the stone slabs that form the “roof” of the passageway. (Photo AmS)

In the «Pakterhagen» – the area west of royal manor ruins, – the archaeologists found a paved footpath in 2012. This footpath runs alongside the walls of the ruins, and we believe that this was the path used by the king when he entered the church. The door to the west was the king’s entrance.

See: Avaldsnes – Norway’s Oldest Royal Seat

SECRET PASSAGEWAY DISCOVERED IN 1986

Stories were told of several “secret passageways” at Avaldsnes, but most people thought they were just old wives’ tales.

In 1986, the Archaeological Museum of Stavanger conducted a short archaeological study on the site of the car park just south of the church and actually found a secret passageway which ran towards the church tower and then turned in the direction of the strait of Karmsundet. About 36 metres of this underground passageway were uncovered before work had to be called off due to heavy rain. A passageway of this kind is a unique find in Norway; only the passageway between the bishop’s palace and the church at Skálholt in Iceland is comparable.

The studies carried out in 2017 by the Royal Manor Project reveald that this secret passageway leads into the newly discovered royal hall. However, the exit to the passageway was not opened because it is crossed by a high-voltage cable just outside.

We assume that the passageway was used as an escape route in times of trouble.

Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle.

The legend tells that doomsday will come when the top of the stone touches the church wall. (Photo Marit S. Vea).

SEE DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE MEDIEVAL ROYAL MANOR. ARKIKON

ST. OLAF’S CHURCH BECOMES A COLLEGIATE CHURCH

Håkon V Magnusson, the grandson of Håkon Håkonsson, appointed St. Olaf’s Church as one of four collegiate churches in Norway. A collegiate church was one in which the king could educate priests and advisors loyal to the throne. The other collegiate churches were in Oslo, Bergen and Tønsberg. The Church of St. Olaf at Avaldsnes is the only one of the four still standing today.

ST. OLAF’S CHURCH – BUILT ON A PAGAN CULT SITE

It is believed that the Church of St. Olaf was built on the site of a pagan place of worship where there were three, possible five, enormous bautas. Written sources tell that one of the stones was 8.2 m high.

Today, only one – the 7.3 metre high standing stone called “Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle” – still stands in its original position. Its name is derived from the runic inscription on the stone: «Mikjall Mariu Næstr» (Archangel Michael, second in rank after the Virgin Mary). Legend has it that Doomsday will come when this standing stone touches the wall of the church. In the dead of night, the church priests therefore knocked pieces off the top of the stone, in order to save the world from doom. Håkon Håkonsson, too, had respect for this stone: the wall of the church was built on a slant to avoid it coming into contact with the stone.

Pilgrim routes in the Avaldsnes area.

ST. OLAF’S CHURCH AS A PILGRIM DESTINATION

When Håkon Håkonsson was crowned, the bishops wanted him to hold the land as a fiefdom of St Olaf and the church. But King Håkon refused to acknowledge Saint Olaf as his overlord. Nevertheless, he dedicated the church at Avaldsnes to St. Olaf. The sagas relate that Håkon Håkonsson tells the old Birchleg Helge that God, the Virgin Mary and St. Olaf are his ombudsmen. We know that during the period of Catholicism in Norway, the church had three altars – one was dedicated to St. Olaf and one to the Virgin May. The third was probably dedicated to Archangel Michael.

About 1075, Adam of Bremen writes that the main pilgrim route northwards to St Olaf’s tumb in Nidaros was the shipping lane and St. Olaf’s Church at Avaldsnes was an important place for pilgrims to stop while on their way to Nidaros.

A hostel was built to shelter pilgrims and other travellers. But pilgrims also came to Avaldsnes by way of the land, as names like «Fegensbrekkå» (the first place one saw the church) and «Munkaskaret» («pass of monks») bear witness to. Furthermore, the Well of St. Olaf, where pilgrims planted crosses and prayed for salvation, is situated at Torvastad, about 2 kilometres northwest of St. Olaf’s Church. Indeed, several legends about St. Olaf are connected with the area around Avaldsnes. (See Legend about St Olaf)

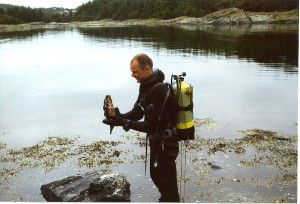

This shows the inner harbour area known as the Kings’ harbour. The remains of sea-related activities in this inner harbour is probably older than the Medieval Period because it would be too shallow to use after the Viking Age. (Photo: Marit Synnøve Vea)

THE HARBOUR AREA OF THE MEDIEVAL ROYAL COURT

Between 2000-2012, various archaeological studies were carried out in the sea, starting in the summer of 2000, when the Stavanger Maritime Museum and the Archaeological Museum in Stavanger began to investigate the harbour area. What they found was a very well preserved medieval harbour – the first time a harbour connected with a royal court has been discovered in Norway. The most striking finds pointed to the activities of the Hanseatic League here. This led to the initiation of a large-scale “Hansa Project” which also involves collaborators from other countries.

While the archaeologists were attempting to define the extent of the Hansa’s harbour, they also came across an older harbour going back to the time of King Sverre and Håkon Håkonsson, i.e. from the end of the 12th century until around 1250.

See: Her finn marinarkeologen truleg hamna til kong Håkon den fjerde

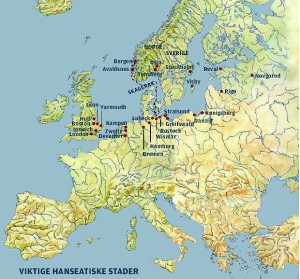

THE HANSEATIC LEAGUE AT AVALDSNES

From the latter part of the Roman era until the year 1000, trade between Norway and central Europe was plied between the countries around the North Sea. Gradually from 1100 and onwards, this trade was controlled by the “Hanseatic cities” which developed a great economic and military power.

Marine archaeologist E. Elvestad with a Siegburg pot. Among the pottery, there are very much sigburg ceramics. Siegburg jars of wine are not considered to be commodities, but intended for the Hansa traders themselves. This suggests that the Hanseatic League has a permanent settlement at Avaldsnes. (Photo Anita L. Arnøy)

The Hansa merchants were never well regarded, but because Norway was dependent on goods like corn, malt, flour and salt, even the powerful Håkon Håkonsson was obliged to let them continue with their trading activities.

In the book “The Norwegian Sow” from 1584, written by a German, we learn that the Hanseatic merchants established their first trading station in Norway at Nothaw, but because they were constantly attacked by pirates there, they moved to a safer place further inland: Bergen.

TRACES ON LAND AND IN THE SEA

A great number of archaeological finds have been discovered both on land and in the sea: boathouses, quay foundations, mooring and ballast stones and quantities of pottery. Several shipwrecks have also been found, for example a very well preserved medieval vessel.

On the seabed, there is a 2.5 metre thick layer of mud and quantities of pottery from the Middle Ages have been found in the top layers of this mud. We have as yet no idea what may be hidden lower down in the mud.

A clinch built ship dated to 1395 lies in the inner harbour. It is very well preserved by the tick layer of sludge. Originally the ship was 22 m long. Naval shipworms have eaten the upper strakes, and the wreck is now 18 m long and 6 m wide.(Photo Rudolf Svendsen)

So far, only a superficial study has been conducted. It may take as long as 20 years to carry out a thorough archaeological investigation of the harbour at Avaldsnes.

Read more: Archaeological evidence of medieval trade in Avaldsnes.

NOTHAW

Old documents and charts show that the Hanseatic trading station of Nothaw/Notau was located at Karmsundet and for about hundred years, people have speculated where Nothow was located. Most believed that it was situated just below the church at Bukkøy, where the names Nottå and Nåttåhavn still exist. These were in fact two well-functioning harbours which were used throughout the period when sailing ships plied the Norwegian coast. The ships sought shelter there during the night and waited until the strong sea current of Salhus two kilometres to the north became calm enough for them to continue their journey.

NOTHAW/NOTAU IS DISCOVERED

The quantities of German and Dutch pottery lying in the top layers of mud mean that we can now confirm that the Hanseatic trading station of Nothaw/Notau has at last been found to be an integral part of the royal harbour at Avaldsnes.

Marine archaeological examinations in 2010. (Photo Pål Nymoen)

AVALDSNES – A ROYAL FREE-HARBOUR?

Nothow’s central location in the middle of the shipping fairway, the royal court at Avaldsnes, the royal chapel and Avaldsnes’ role as a meeting place for the medieval court up until the first half of the 14th century may have been the reasons why the Hansas spent the winters here. Bergen gradually established itself as Norway’s first real capital city and towns began to develop in other parts of Norway. As the Hanseatic merchants tightened their grip on Norway’s export trade, trading became increasingly concentrated in and around the towns.

One might therefore think that Avaldsnes would lose its importance as a Hanseatic harbour, but the Hanseatic pottery found at Avaldsnes appears in large quantities at the very time that we might expect to see a decline. One of the reasons for this may be that Avaldsnes was granted status as a “libero portu Regio”, or royal free harbour.

THE HANSAS BURN THE ROYAL COURT AT AVALDSNES

In 1367, it came to open conflict between the Hanseatic League and Haakon VI. The following year, the Hansas set light to the royal court. But they must nevertheless have come to an agreement with the king, because the findings of Hanseatic pottery found on the seabed outside Avaldsnes date from as late as up to the 16th century. It appears that at some point during the 15th century, the Hansas took over the power that was previously in the hands of the kings at Avaldsnes.

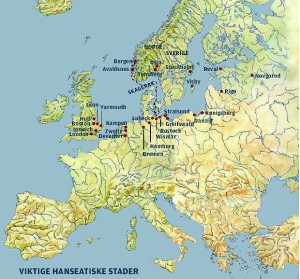

IMPORTANT PLACES FOR THE HANSA TRADERS

Illustration Dag Frognes. After E. Elvestad, A. Opedal and F.Fyllingsnes,

CONTEMPORARY SOURCES

A few written documents giving information dating from the time of the royal court at Avaldsnes in the Middles Ages have been preserved. Some of these are royal letters. The oldest is from 1297, while five letters were written in the years 1308 – 1214, when Håkon V Magnusson was king. Håkon V also mentions the royal church at Avaldsnes in his will.

Another, less pleasing document from the times is the description of how the Hansas burnt down the royal court at Avaldsnes in 1368. The Royal Court at Avaldsnes was probably also used after the ravages of the Hanseatic League. At least Haakon VI issued a royal decree on Avaldsnes in 1374. This is the last known royal letter written here in medieval times. When Christian I in 1453 negotiated in Nothaw with the deposed Archbishop of Nidaros, there is no mention of the royal estate at Avaldsnes. It therefore appears that Avaldsnes ceased to be a royal residence sometime between 1374 and 1453.

Last update November 2022

Back