Celtic Iron Age (500 BC – 0)

Waterloo Helmet, London. Celtic helmet with horns, used in ritual contexts. 150-50 BC Now the British Museum. (Photo Wikimedia Commons)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

The first part of the Iron Age is called the Pre-Roman Iron Age or the Celtic Iron Age because of the Celts who dominated Europe at this time. Knowledge about iron production reached Scandinavia during this era, and this may be due to the migrations of the Celts.

Germanic tribes also start migrating at this time. A number of the Germanic ethnic groups later to be found further south in Europe asserted that they actually come from “Skandza” – a country in the North. Their migration from Scandza may have begun during the Celtic Iron Age and the movements they are believed to have made northwards during the centuries after the birth of Christ can therefore have been a “homecoming”.

NORWAY DURING THE CELTIC IRON AGE

The Celts have left behind fantastic finds, both on the Continent and in Britain. We find traces of Celtic influence in Denmark too. However, in Norway there is a dearth of finds from the Celtic Age. Some believe that this is because of the cultural decline caused by climatic change – the Filbulwinter, a harsh winter, that we hear about in Norse legends. Others believe that the advance of the Celts in Europe hampered trade and cultural exchanges between the North and the rich lands around the Mediterranean, but this lack of finds may just as easily be due to changes in burial customs.

It is possible that tribes in Norway wandered southwards to the Continent. If this is the case, there are few physical clues to suggest that they kept in contact with their homelands. One exception is the Kolstø grave in near Avaldsnes, which is one of 2-3 weapon graves from the Celtic Iron Age in Norway and the only we know of in the whole of Western Norway.

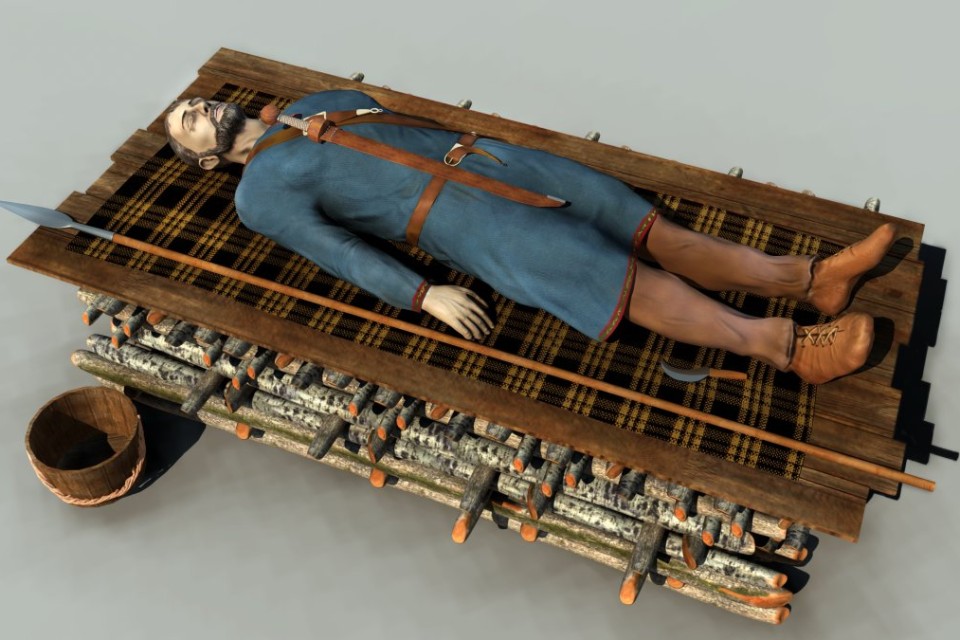

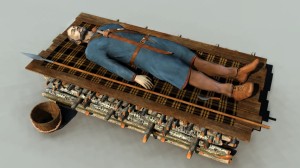

The chieftain’s burial in the Os Mound on Kolstø at Avaldsnes. Celtic Iron Age. (Ill. Ragnar Børsheim)

THE WEAPON GRAVE AT KOLSTØ

At some point during the last 200 years of the Celtic Iron Age, a powerful man or chieftain was buried in what we call the Os Mound (Oshaugen) at Kolstø, just south of Avaldsnes itself. The mound was originally large in size, 2-3 m high and ca. 25 m in diameter. It was clearly visible for those passing through the strait of Karmsundet.

In 1894, objects from this grave were handed in to the Archaeological Museum in Stavanger (AmS), together with a spearhead from the Viking era which lay in the same mound. The iron objects were in a poor state of conservation and were therefore overshadowed by burial finds of a higher quality which were discovered in the area around Avaldsnes during the decades before and after 1900.

In 1984, the Danish archaeologist Jørn Lønstrup came to the Archaeological Museum in Stavanger, studied the weapon graves at the museum and discovered that finds from the Os grave included a sword and a ferrule from the Celtic Iron Age – a period of which there are few traces in Norway. Per Haavaldsen at AmS subsequently examined the material from the Os Mound grave.

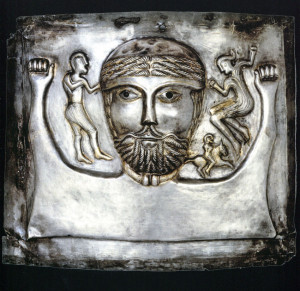

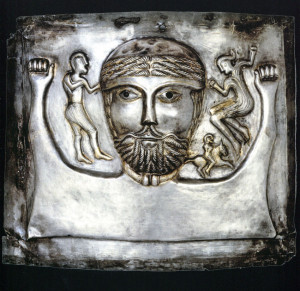

Face from the Gundestrup cauldron. The ring around his neck is called a torque. (Photo Archaeology in Europa)

Haavaldsen came to the conclusion that there were after all links between Karmøy and the rest of Europe during the Celtic Age. The man buried in the Os Mound must have been a person of special standing – perhaps a chieftain – and he was buried with a full array of weapons, in line with the custom at this time on the Continent:

– a short, one-edged iron sword. Only parts of the sword and blade is preserved

– the ferrule of a sword sheath

– a long spear or lance with an iron tip

– the man was probably also buried with a shield

– a small-sized curved knife made of iron. Knives of this kind were placed in Celtic graves as a mark of the deceased’s high status

– an iron fragment belonging to what is believed to be a torque, a neck ring.

The torque is extremely distinctive. On the Continent, the Celtic chieftains used gold or bronze torques as a symbol of power. The Celts were the dominant ethnic group in Europe and this custom was copied by groups outside the Celtic cultural area. In Western Norway, the remains of a bronze torque were found at Sørbø, Rennesøy, and a torque of iron was found at Etne.

The warrior grave at Kolstø is evidence that people living in the area around the strait of Karmsundet during the Celtic Age also had links with, and were influenced by, people on the Continent: they followed continental fashions in weaponry and clothing and even developed a local version of the chieftain symbol – an iron torque. Iron torques are unknown in the rest of Europe.

See: Per Haavaldsen: Den glemte høvdingen. En våpengrav fra eldste jernalder på Kolstø. Frá haug ok heiđni, 2000:3:9–12.

The settlement at Munkhaug had a clear view in all directions. In the background to the north-east we see Olav’s Church and the Karmsund Bridge. (Photo from Excavation Report, Rogaland County, K..S Eilertsen)

SETTLEMENT AT MUNKHAUG, AVALDSNES

Traces of a settlement, including holes originating from posts from houses, have been found on the Avaldsnes peninsular. But we do not know whether the main building belonging to the ruling chieftain’s family was situated on the peninsula during the Celtic Age. In any case, traces of several buildings from Celtic times were discovered at Munkhaug in 2011, i.e. at the entrance of what is today considered the boundaries of the Royal manor area. Was this where the man or chieftain in the Ols Mound lived?

The settlement at Munkhaug was discovered when archaeologists from Rogaland County Council were carrying out investigations in connection with a regulation plan. They found a large quantity of building postholes and wall trenches remaining from several trestle-frame houses which appear to have been rebuilt during the settlement period. Several fireplaces, cooking pits and traces of what may have been an enclosure for animals were also found in the trenches. The site is located on a ridge with good drainage and a clear view in all directions.

THE MYSTERIOUS FACE MASKS FROM AVALDSNES

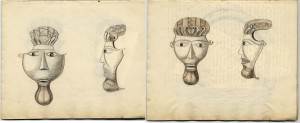

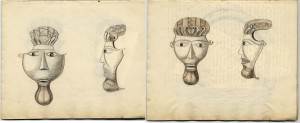

Around 1800, a gilt bronze ring and two bronze masks were discovered at Avaldsnes. These were sent to “the Antiquarian Commission in Copenhagen” but have most probably been lost. Nevertheless, we still know quite a lot about the masks and the arm ring because accurate drawings were made of them and they are described in several written sources.

The smaller of the two masks was 13-14 cm, and the larger 15-15 cm, long. The ring had an outer diameter of 17-18 cm and was 1.5-2 cm wide. The masks had openings where the eyes should have been – these were originally filled with glass, stones or some other material. The ring was adorned with inlays of coloured glass.

Copper alloy, face masks found at Avaldsnes in c. 1800. Drawing by Lyder Sagen in 1812. (Photo: Bergen Museum.)

Sources relate that these objects were found “at a depth of several ell in the ground at Augvaldsnæs”. Frans-Arne Stylegar, who has made an in-depth study of these objects, believes that the site of the find may be Kjellerhaugen (Celler Mound), otherwise known as Kuhaugen (Cow’s Mound).

This burial mound, which is situated near the path down to the Nordvegen History Centre, was originally raised in the Bronze Age, but the masks and the ring may originate from a secondary grave in the mound. Kuhaugen (Cow’s Mound) also tallies well with a local traditional tale of a farmer who dug into the mound around the year 1800 and became rich because he found the “collar belonging to King Augvald’s sacred cow”. This “collar” may have been the bronze ring described above.

But which era do these objects come from? Both the masks and the bronze ring are unique – nothing like them has ever been found and it is therefore difficult to date them. Neither do we know where they originally came from or what they were used for. Representations of faces have long traditions, stretching from the Celtic Iron Age and into the High Middle Ages. Based on stylistic details from the Avaldsnes masks, Stylegar and a group of researchers put forward the theory that these objects stem from the Celtic Iron Age or the Viking Age.

Copper alloy ring found at Avaldsnes in c 1800. Drawing made by Lyder Sagen in1812. (Photo: Bergen Museum)

The Celtic Iron Age: Details from the Avaldsnes masks can be recognised in other Celtic crafts, such as locks of hair over the forehead, point decorated eyebrows and eyes made of another material than bronze. It is therefore possible that the Avaldsnes masks could have come from a Celtic area or an area influenced by Celtic culture.

The Viking Age: The Avaldsnes masks have features that are recognisable from Anglo-Irish material from the 8th – 9th century, for example masks fixed to hanging-bowls. Bowls of this kind were originally used in religious rites and many have been found in Western Norway – as a result of Norwegian Vikings’ activities in Britain.

Details on the Avaldsnes masks may also be linked to Scandinavian finds from the Viking Age. For instance, the shape of the mouth and the double row of teeth resemble features of the three heads on the Oseberg wagon. The same applies to the hatched and twirled moustache and the heavily emphasised line of the eyebrows.

Read more: Two masks and a ring from Avaldsnes in Rogaland

Prevalence of the Celtic culture in the first centuries BC. (Source. Francisco Villar i “The Indo-Europeans and the origins of Europe” – Ill. Wikimedia Commons)

THE CELTS GAIN POWER IN EUROPE

From ca. 800 BC, the Celtic Hallstatt culture from Austria controlled the bronze trade with the Mediterranean countries. From their core area in Central Europe, the Celtics extended their power so that by 500 BC, they controlled an area stretching from the Black Sea to Ireland.

It is at this time that the name Kelto (= Celts) is first mentioned in written sources from the Mediterranean and the Celts first start using iron. We are entering the first part of the Iron Age, called the Age of the Celts. From this time onwards, bronze became less accessible in Europe.

Last update November 2022

Back