Merovingian period (550 – 750 AD)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

Detail of the fortress that was found at Avaldsnes in 2012. The stone walls are now covered again. This to conserve the ruins that was not completely excavated. (Photo Ørjan Iversen)

At the advent of the age named after the royal Frankian dynasty, a paradigmatic shift in cultural history occurs: both verbal and visual language becomes simpler, most of the graves lie under small mounds or on flat land and jewellery made of precious metals becomes a rarity. This is also the age when many farms lie abandoned and archaeological finds are few and far between. The decrease in findings has been interpreted as a social decline caused by climate change, the plague or wars.

A MEROVINGIAN FORTRESS FOUND AT AVALDSNES

In 2012, the Royal Manor Project made an exciting discovery which suggests that the kings at Avaldsnes were expecting to be attacked: They built a fortress in order to protect the settlement inside its walls. The fortress at Avaldsnes was constructed some time between 600 and 800 AD, most probably before the Viking Age. In other words, the rulers at Avaldsnes must have felt threatened at this time and we can read about such times of strife in the heroic sagas.

The fortress at Avaldsnes is the only fortified settlement from prehistoric times that has been found in Norway. It was situated in a strategic position on a hillside to the east of the outbuilding, commanding a wide view over the strait of Karmsundet. The stone construction is only just 4 metres wide, extending from the burial mound we call the Cellar Mound and continuing about 30 metres southwards, along the edge of the slope.

We do not know how far the fortress walls stretched and how large the area inside the walls originally was. In Norway, there are a number of hill forts that were built in rural areas during the Roman Age and the Age of Migration. The construction of the fortress at Avaldsnes appears to resemble hill forts of this kind, which were uninhabited fortifications on hilltops, where local people could seek refuge if they were attacked. However, the fortress at Avaldsnes differs from these in that it was built for the purpose of protecting a farm which already existed

“Workshop” area for forging, handicraft, grain drying, salt production etc.. (Photo Ørjan Iversen)

The stone foundations were probably encased in timber that served as a support for an outer palisade of vertical stakes. Those defending the fortress would have stood on the wooden floor inside, where they could stand protected and defend themselves with bows, arrows and spears against the attackers struggling up the slope.

THE WORKSHOP AREA

Inside the fortress lies the “production area” or workshop area. Here, we have found many holes originating from posts from small houses, hollows, trenches, ovens, fireplaces and forges. These finds mean that this area was used for different kinds of workshop and handicraft activities during the period between 200-1000. Forges of different kinds were in use and corn was dried here – a necessary task, if the king and his followers and guests were to be fed. They also produced black salt by burning seaweed.

THE SALHUS MOUND (SØLUSHAUGEN)

Only a very few large burial mounds from the early part of the Merovingian Age have been found in Norway. One of them is the Rakne Mound, located in Romerrike and dating from ca. 550 AD. Another is the Salhus Mound at Avaldsnes, dating from the end of the 6th century/the beginning of the 7th century. No funeral remains were found in these two strange mounds and it is possible that they were not burial mounds at all, but rather memorial mounds, perhaps dedicated to people who had died a long way from home or at sea.

The Salhus mound lay on a plateau on the border between Gunnarshaug and Nordbø. (Photo Marit Synnøve Vea)

Once there were many burial mounds along the strait of Karmsundet and there has been some doubt as to which of these lost mounds was the original Salhus Mound. Because of its name, it was thought to lie at Salhus, near Karmsund Bridge. But this is probably not the case: according to the earliest written source about this topic, Salhus was situated on Gunnarshaug Farm on the border of Nordbø.

The Salhus Mound was examined by Shetelig in 1906 and 1912. Brøgger conducted a minor archaeological excavation in 1908. Before these studies, the Salhus Mound was 43m in diameter and between 3.8 – 4.1 metres high, but a great deal of material was removed before the measurements were taken. During the excavation, it was assumed that its original height was about 5m. Its location on the plateau must have made it look even higher. The northern end of the mound was built over a smaller mound with a diameter of 13.8m and a height of 2.7m (Shetelig 1912b, summary by Ringstad 1987:66).

The mound consisted of layers of grass turf and sandy soil and towards the bottom, coal and sand was found. To the east and north, the inside of the mound consisted of a mass of stones up to 1.5m thick. The mound lay on a rock bed and the base was flat and smooth. Several shafts were dug into the mound, but it was never completely excavated. No grave was found, but Shetelig concluded that it was possible that there was a grave in the mound.

1. Shipburial Storhaug, 2. Salhus Mound. 3. Salhus mounds. Once there were numerous burial mounds along the Karmsund. Alone from the farm Gunnarshaug we know 13 mounds. (Photo Gunnar Strøm)

THE FORGOTTEN HEROES OF THE MIGRATION PERIOD AND THE MEROVINGIAN PERIOD

The poems about heroes and gods, which were recited in the Viking Age, were actually about people and events from the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period. The same applies to the heroic sagas.

These poems and stories are of course coloured by the times in which they were told, but we may nevertheless question why none of them give us the impression that poverty and isolation were characteristic features of these two ages? For the people portrayed in these stories, the North Sea and the Baltic Sea were a common playground and journeys backwards and forwards between the Nordic lands were as commonplace then as ferry trips to Hirtshals or Kiel are to Norwegians today.

King Augvald was one of the kings who is supposed to have lived around the year 600 – a transition phase between the Migration Period and the MerovingianPeriod. According to the sagas, it was he who gave Avaldsnes its name. The story goes that Augvald came from afar and drove the earlier rulers out. He then settled at Avaldsnes, which was named after him.

According to the old genealogies, King Augvald had a son called Jøsur. Jøsur had a son called Hjør. When Hjør died, his son Hjørleiv with the nick name “women lover”, took over as king. Hjørleiv travelled far north, to Bjarmland and also conquered a kingdom in Denmark. He died away from home, while on a Viking expedition. Two of his sons, Ublaud and Halv, are mentioned in Halv’s Saga and the Icelandic book of Landnáma. And as this King Half came to power, we have entered the Viking Age.

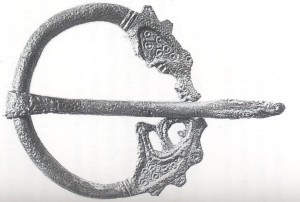

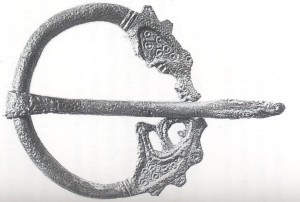

Ring Buckle with two dragon heads from Ferkingstad. Found in a woman’s grave, dated to between 725 – 800 (Photo AmS)

THE MEROVINGIAN PERIOD AT FERKINGSTAD

Many findings from the Merovingian Period and the Viking Age have been found at Ferkingstad, which is situated on the west side of Karmøy. One example is a burial site with five cremation graves on flat ground and without mounds over them. These include a man’s grave, two women’s graves, a grave whose objects give no clear indication of the gender of the corpse and a boat grave with two bodies. Another woman from Ferkingstad who died during the 8th century was buried and covered with a small mound. Amongst the objects buried with her were two oval brooches of the so-called Berdal type..

THE MEROVINGIAN PERIOD: A TRANSITION PHASE

The Merovingian Period is a transition phase between the Migration Period and the Viking Age. The Merovingian Period is usually said to belong to the Early Iron Age, while the Later Iron Age begins with the Merovingian Period and continues on into the Viking Age.

The Viking Age is traditionally defined as the time between two historic events: the attack on the Lindisfarne Monastery in 793 and the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. However, archaeological research and findings indicate that the Viking Age must have begun around the year 750 and some scholars even believe it began as early as the year 700.

Oval brooche from a woman’s grave found at Ferkingstad. Note the ornamentation with two seated people. Brooches like these were used in pairs to hold up a woman’s over-dress.(Photo AmS)

EVENTS ON THE EUROPEAN MAINLAND

The Merovingians were a Frankian dynasty which established a kingdom during the 6th century in the area that is now France and parts of Germany. During the 8th century, the Arabians advanced northwards from Spain and it was not the king, but the king’s chief courtier, Karl Martell of the Carolingian dynasty, who warded off the Arabian attack. This marked the end of the Merovingians’ ancient royal dynasty and the Carolingian dynasty then came to power.

In Sweden, this transition phase is called the “Vendel Era” due to rich archaeological finds discovered at Vendel in Uppland. Large burial mounds in Uppsala also stem from this time.

Last update November 2022

Back