Nordic Bronze Age (1800 – 500 BC)

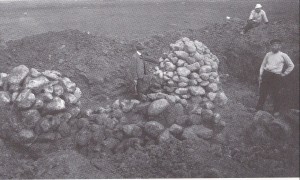

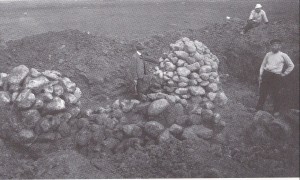

Old photo showing some of the burial mounds on Reheia/ Blood Heights. The name Blood Heights comes from a battle between Haakon the Good and the sons of Eric Bloodaxe which took place here in 953.

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

PEOPLE WHO SHAPED THE LANDSCAPE

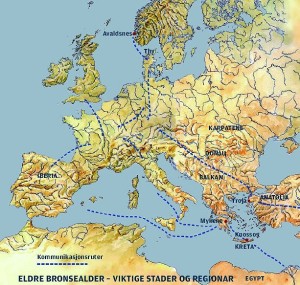

During the Early Bronze Age over 3000 years ago, the people living in the area around the strait of Karmsundet shaped the landscape by building monumental burial mounds. They built enormous mounds on “sacred” sites and the sun was worshipped as a major deity over large geographical areas. The Karmsundet population was at this time connected with an international trade and contact network stretching from the Mediterranean Sea in the south to Russia in the east and Ireland in the west. People of the greatest importance in society – i.e. political and/or religious leaders or persons of symbolic standing – were buried in large graves of earth and stones.

BURIAL MOUNDS OF EARTH AND STONES

Burial mounds dating from the Bronze Age can be found all over Karmøy, from Skudenes in the south to Torvastad in the north. Some of these Bronze Age burial mounds were also used when people in the Iron Age wanted to bury their dead kings and chieftains. The mounds, covered with green turf, are situated on ridges, often alone, but sometimes several can be found in one place. The most prominent example of a group of burial mounds is those at Blood Heights, which lies on a geographical line joining Karmsundet in the east with the sea to the west.

Arm ring of gold from Prinsahaug. The gold mixture has a lot of silver and a small amount of copper. Probably this gold came from Ireland. (Photo Bergen Museum)

Other earth mounds worth mentioning are Kjørkhaug and Kubbhaug, which are located just north of Blood Heights, while the third and northernmost area where earth mounds can be found is at Storasund, on the northern tip of Karmøy. These earth mounds around Karmsundet are considered to be the northernmost outpost of the “Danish” Bronze Age culture. Perhaps they were originally made by immigrants from Denmark who arrived here at some time over 3000 years ago.

At Karmsundet, there are also cairns made of stones dating from the Early Bronze Age, where the burial chamber is covered with heaps of stones. Since the graves in these stone mounds are not so well protected, the skeletons and burial gifts have often been destroyed. But judging by the small amount of material we have found, it appears that at least some of the stone graves were constructed at the same time as the earth mounds. We do not yet know whether these two types of graves are expressions of different sides of the same religion or whether they represent two competing cultures.

THE POWER CENTRE AT ITS PEAK

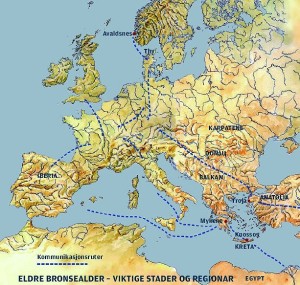

The chiefdom which arose around the strait of Karmsundet during the Early Bronze Age had close contacts with equivalent power centres further south. Society here was part of a European system of trade contacts stretching from the Mediterranean to Karmsundet and from Ireland to Russia. The large mounds were constructed as the last resting places of these powerful chieftains who cultivated international contacts.

Based on the objects found in the graves, the mounds at Karmsundet are for the most part thought to date from period III, which means that the Bronze Age culture at Karmsundet seems to have reached its peak during the period from 1380-1100 BC. However, a C-14 dating of a sword sheath from the Chieftain Burial 5 at Blood Heights led to a dating between 1490-1320 BC, i.e. the transition between period II and III

Bendiksen’s map of the ancient monuments at Blood Heights from 1876 (Topographic Archives, Oldsakssamlingen Oslo)

THE BURIAL MOUNDS AT BLOOD HEIGHTS (REHEIA)

Reheia is called Blood Heights because a terrible battle between Håkon the Good and Eirik Bloodaxe’s sons is said to have been waged here in 953. The ridge is located in the proximity of Avaldsnes and from the top, there is a good view over the royal seat. On this ridge, halfway between the open sea and the strait of Karmsundet, a row of enormous burial mounds was erected in the Early Bronze Age. The mounds were from 5 – 7.5 m high and about 30 m in diameter. A series of smaller mounds lay between and around the large mounds.

The mounds at Blood Heights fell prey to man’s thirst for gold and to excavations at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1873, over 40 graves were nevertheless registered on the ridge: 7 monumental burial mounds, 28 smaller mounds, 7 square stone pavings, 1 standing stone and the foundations of other mounds that had already been removed. Today, only 6 large mounds are visible in the terrain.

Four bronze swords are found by the strait Karmsundet. This is from “The Chieftain Burial 5″ on Blood Heights. It consists of three parts and is 52.4 cm long. (Photo Oldsakssamlingen, Oslo)

The burial site at Blood Heights originally consisted of 8 huge and at least 50 smaller burial mounds. The huge burial mounds, built on a “straight line” from east to west (see Bendiksen’s map), date from the Early Bronze Age, even though secondary graves from the Iron Age have also been found here. The smaller mounds (now removed) were traditionally thought to be Iron Age graves, but they, too, may have been from the Bronze Age.

The burial mounds at Blood Heights are what we call “earthen mounds” – they are built of turf and earth laid over an inner core consisting of a heap of stones. It took several thousand man-days just to build one of these barrows and enormous human and material resources were required in order to build them.

Four of the Bronze Age mounds on Blood Heights viewed from above, the closest is Fyrstegrav 5, then Prinsahaug, then Barnegraven. (Photo: Norsk Flyfoto AS)

BURIAL MOUNDS ADDRESSING THE HEAVENS

While the large number of burial mounds along Karmsundet built during the Iron Age were placed there so that people sailing through the strait could see them, the barrows of the Bronze Age are directed at the heavens.

Perhaps they were positioned like this so that the sun god could find his way across the sky? In any case, it is only when you are in an aircraft and can look down on the whole area from above that the monumentality of these barrows becomes apparent. Was it just to impress their contemporaries that people in the Bronze Age built such majestic burial mounds? What were their death rituals like and what did they believe in?

FYRSTEGRAV 5 (CHIEFTAIN BURIAL 5)

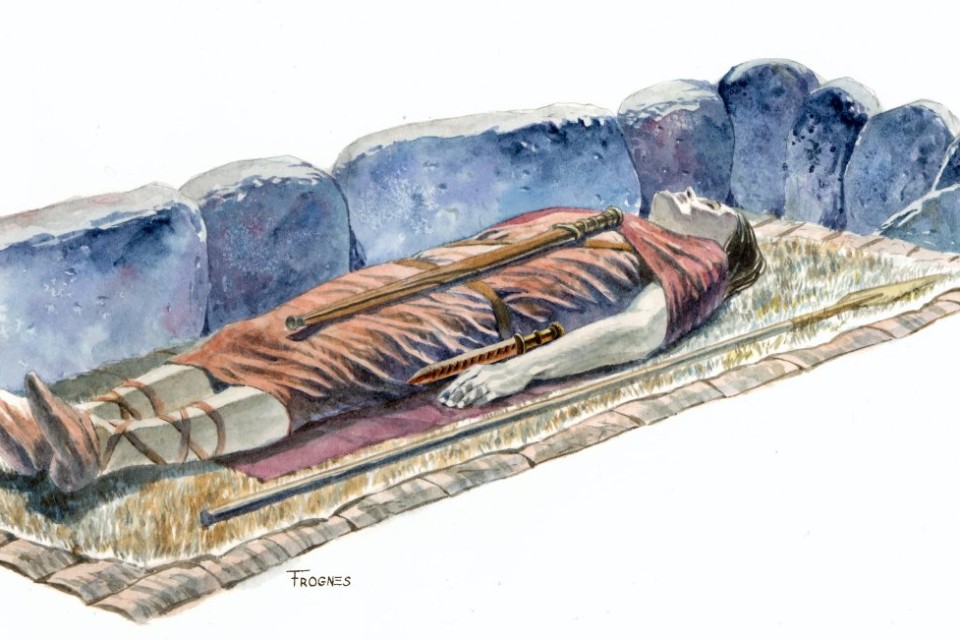

The “Chieftain Burial 5″ dates from 1490-1320 BC. It seems that this mound may be the oldest at Blood Heights. Before excavation, the mound measured 30 m across and had a height of 6 m. To day it is 5 m high.

Inside the mound, the skeleton of a man was found. He lay on birchbark in a burial chamber clad with flagstones and was clothed in woollen garments with double buttons made of bronze and a bronze buckle. A bronze dagger lay at his feet and a sword lay on his breast. Beside him, there was a sword sheath made of calf leather and a spearhead.

PRINSAHAUG (PRINCE MOUND)

Before excavation: width 30 m and height 7.5 m. Today: width 30 m and height 5 m. According to local tradition, this burial mound is that of Prince Guttorm, son of Eirik Bloodaxe, who is reported to have fallen at the “Battle of Bloodheights” in 953. The mound is also called Guttormshaug (Guttorm’s Mound), but we now know that this mound already was around 2300 years old when “Prince Guttorm” died.

The Prince Mound also called Guttorm’s Mound. Snorri says that Guttorm, som of Eric Blooaxe, fell at the Battle of Blood Heights. Perhaps the bauta was erected in his memory? And perhaps people later also linked his name to the mound? (Photo Marit S. Vea)

When the burial mound was examined, a burial chamber with a bronze sword, small pieces of gold leaf and an arm ring of twisted gold were found. Gold was rare in the Bronze Age. Arm rings of this kind are believed to have been alliance rings symbolising political power. The ring is of 23-carat gold mixed with a considerable amount of silver and a little copper. The gold probably came from Ireland.

The chieftain laid to rest in the Prince Mound may have acquired the bangle from Denmark. The arm ring and other objects from Blood Heights indicate that there were political and religious alliances with the area south of Lim Fjord and further down towards Schleswig-Holstein and the northern part of Lower Saxony

BARNEGRAVEN (THE “CHILD’S MOUND”)

Another of the burial mounds is called the “Child’s Mound”. It was originally 30 m wide and 6.5 m high. After excavation: 22 m wide and only 3.2 m high. Many of the stones from the inner construction in the mound were used to build walls in the surrounding area. The remains of a child’s skeleton were discovered in the grave. Since the flagstone coffin lay inside the mound of stones itself, we believe that the mound was built over this child.

It is possible that the child was given such a magnificent burial because he or she was a much-loved child of a chieftain. It could also be that the people who lived at Avaldsnes over 3000 years ago believed that this child had very close contact with the gods and had therefore to be honoured in a special way after his or her death.

Excavation of Kjørkhaug in 1905. We see two of the seven cone-shaped cairns that lay inside the mound. (Photo Bergen Museum)

KJØRKHAUG (CHURCH MOUND)

The enormous barrows at Blood Heights are the ones that attract the most attention, but other Bronze Age mounds on North Karmøy, such as Kjørkhaug at Gunnarshaug, also contained interesting secrets. Kjørkhaug was opened by Shetelig in 1905. The bronze blade of a dagger dating from between 1380-1100 BC had already been discovered there. A spiral ring made of gold and a mosaic bead (now lost) from the Iron Age were apparently discovered and these objects may have come from secondary graves.

No grave was discovered inside the stone mound itself but instead, seven mysterious, cone-shaped stone cairns. During the time of excavation, these were regarded as “alters”. Later on, Kjørkhaug has been interpreted as a cenotaph – the cairns were believed to be memorials to seven people who died somewhere else. Shetelig wanted to excavate the mound in its entirety but did not have enough time. Sections of the inner core may therefore still be preserved.

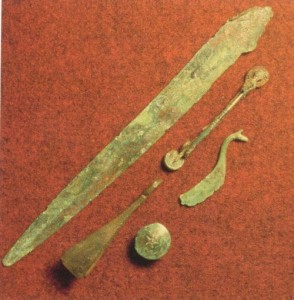

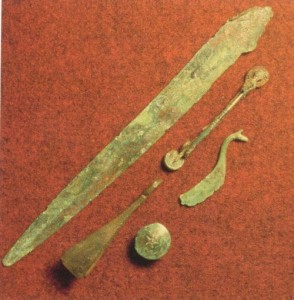

Finds from Kubbhaug: A dagger, fibula, a button, tweezers and a razor adorned with a beautiful animal head. (Photo Bergen Museum)

KUBBHAUG (DOOM’S MOUND)

Kubbhaug is located just north of Church Mound. It was partially excavated by Shetelig in 1905 and turned out to be a more traditional, stone burial chamber covered by two flagstones. Parts of a skeleton were found here. The dead man had been buried with a dagger, fibula, a button, tweezers and a razor adorned with a beautiful animal head. The razor and the tweezers were “toiletries” used by men in the Bronze Age. These finds show that they cared about their appearance and that they were perhaps clean-shaven?

RINGENRØYSA – (RING CHAIRN)

Ringenrøysa is located in close proximity to the strait of Karmsundet, on ground now belonging to Norsk Hydro’s Karmøy Factories, just south of the royal court at Avaldsnes. The stone mound was opened in 1963, when the site was being surveyed prior to the construction of the aluminium works. When the stone barrow was examined, it was 43 m long, 18 m wide and 2.5 m at its highest point. Seafarers who anchored their ships by Høyevarde lighthouse had used stones from the mound as ballast.

On the north side of the mound’s centre, there was a 6 m long and 3 m wide series of stones positioned in the shape of a boat, which looks as if it is sailing in or out of three parallel stone circles. The innermost circle, with a height of about 1 m, was best preserved. The stone circles were probably erected as an imitation of the sun. Perhaps it is this vessel that was to carry the dead back to the sun, from where all souls were believed to originate? Or do the circles allude to different stages in the kingdom of death?

Ringenrøysa. A stoneship sailing in or out of three parallel stone circles (Photo Dag Sunnanå)

In the left section of the central ring, there stood a 1.7 metre long chamber made of dry broken stones. At the north end of the chamber, 6 teeth were found and in the middle, there were pieces of a pelvis and hipbone.

RIngenrøysa is also called the King’s Mound, but the person who was buried in the 1.7 m long stone coffin in the middle of the circles was probably a woman. Young women were often buried in sumptuous graves. The woman in the Ringenrøysa may have been a young princess and a religious leader for the people at Karmsundet.

A strange thing worth mentioning: This burial was called “Ring Chairn” also before the excavation when it only looked like a heap and the three rings inside were covered with a lot of stones.

HIDDEN STONE SHIPS

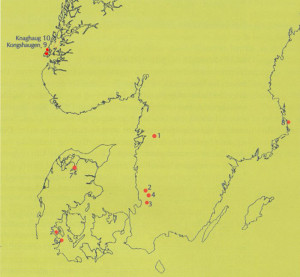

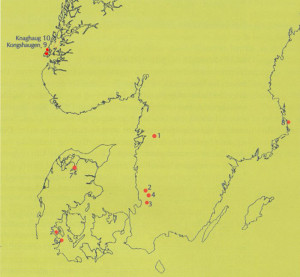

Altogether, 8 barrows or stone mounds containing ships dating from the Late Bronze Age have been found in Scandinavia. Two of these are situated on North Karmøy. One is the stone ship at Ringenrøysa as mentioned above, and the other is a stone ship in Knaghaug which was 3 m long and 2 m wide.

Map with stone ships from Early Bronze Age. (From Lise N. Myhre. “Historier fra en annen virkelighet”, AmS 1998.)

Why did people build hidden stone ships inside burial mounds? Who was meant to see them and where were the ships sailing to?

THE LATE BRONZE AGE

The 7 square stone constructions discovered amongst the barrows at Bloodheights may have been built during the Late Bronze Age. Perhaps they were meant to be a kind of foundation for “abodes of the deceased” where the dead lay while their people performed grand rituals amongst the old Bronze Age mounds. For burial customs changed in the Late Bronze Age: it would appear that the rituals themselves assumed greater importance than building monumental burial mounds.

This change in burial customs may be a sign that people at this time had begun to worship a new deity. It seems that the earth goddess, Mother Earth, plays a more important role than the sun god sailing over the heavens. Large burial mounds ceased to be built and this may be a reflection of greater social equality.

At Avaldsnes, a neck ring was found in a stone mound and two neck rings were buried in a marsh – perhaps as an offering to a female deity. This deity may have been the earth goddess Nerthus. Statues of naked female “dancers” have been found which may be images of this earth goddess. We are now on our way into the Iron Age.

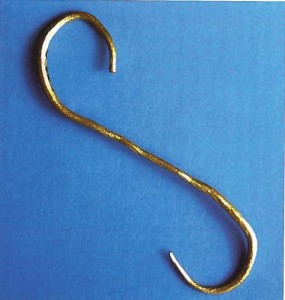

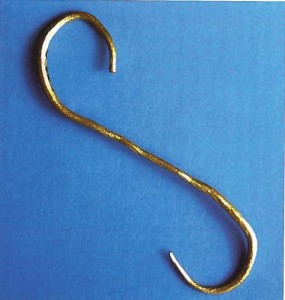

Deformed arm ring of gold from Stange. From the latter part of the Bronze Age. Objects of gold was very rare in the Bronze Age. Why was this the bracelet destroyed. Should it be melted down? (Photo AmS)

About 100 AD the Roman historian Tacitus writes this about Nerthus:

In an island of the Ocean stands a sacred grove, and in the grove a concentrated cart, draped with cloth, which none but the priest may touch. The priest perceives the presence of the goddess in this holy of holies and attends her, in deepest reverence, as her cart is drawn by heifers. Then follow days of rejoicing and merry-making in every place that she designs to visit and be entertained.

No one goes to war, no one takes up arms; every object of iron is locked away; then, and only then, are peace and quiet known and loved, until the priest again restores the goddess to her temple, when she has had her fill of human company. After that the cart, the cloth and, if you care to believe it, the goddess herself are washed in clean in a secluded lake. This service is performed by slaves who are immediately afterwards drowned in the lake. Thus mystery begets terror and pious reluctance to ask what the sight can be that only those doomed to die may see. (J.B. Rives Translation, Tacitus’ Germania, Chp. 40)

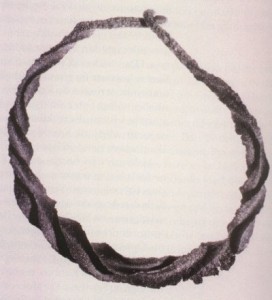

NECK RING FROM KONGSHEIA

At Kongsheia (King’s field), some distance south of Blood Heights, Shetelig registered 56 barrows and stone mounds in 1902. The graves dated from both the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. In one of the smallest stone mounds, a twisted neck ring of bronze was found. Since the mound was so small, we are uncertain whether this was meant to be a burial mound or just a heap of stones cleared from the ground. If the latter is the case, the ring may have been laid in the heap of stones as an offering.

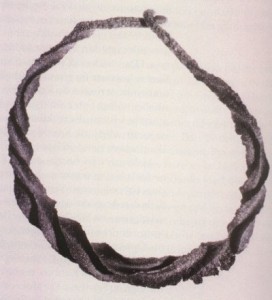

NECK RING FROM KINGS’ FIELD, AVALDSNES

(Foto AmS)

NECK RINGS OF BRONZE FROM VÅRÅ, AVALDSNES

(Photo Oldsakssamlingen, Oslo)

The neck ring is an example of a so-called “wendelring” or torque. It is about 17 cm in diameter. The majority of torques of this kind have been found on the islands of Denmark and as far south as the region west of the Rhine and as far east as the Vistula River in Poland. The ring dates from the last part of the Bronze Age, i.e. ca. 600-500 BC.

NECK RINGS FROM VÅRÅ

In 1854, two neck rings made of bronze were discovered on the moors at Vårå. Double-twisted neck rings of this type are often found in pairs and signs of wear indicate that they were often worn together. One of the rings is slightly larger than the other. These neck rings date from the last part of the Late Bronze Age, i.e. 600-500 BC. They were probably buried in the marshes as an offering to a female goddess. This female deity may have been the earth goddess Nerthus.

Small figures of naked women also reveal that neck rings were worn in pairs. Double-twisted neck rings like this are usually found in Southern Scandinavia, Germany and the areas stretching between the River Weser and the River Oder.

BURIAL MOUNDS – MYSTERIES FROM AN ORAL CULTURE

Like a visible message from a non-writing age, the monumental burial mounds shape the landscape and we try as best we can to interpret the messages from this mysterious culture. The more we discover, the more questions remain to be answered:

Important places, regions and lines of communication in Early Bronze Age

(Ill. Dag Frognes)

In the Early Bronze Age, people at Karmsundet buried their dead leaders in mounds made of both earth and stones. Do these two different ways represent two different burial customs from the same culture? Or were the stone mounds used by people who lived here before a new ethnic group arrived here from Denmark?

The Bronze Age mounds at Blood Heights are just as old and contain equally as rich finds as the Bronze Age mounds in Denmark. Could this be a sign that immigrants migrated here from Denmark? Did the people who built these mounds belong to a ruling aristocracy who overpowered other people living here both culturally and politically? Or did two cultures live peacefully side-by-side within one small geographical area? And did the “immigrants” gradually use the material that was most easily accessible – stone – when they wanted to bury their dead princes and princesses?

Read more: “Historier fra en annen virkelighet. Fortellinger om bronsealderen ved Karmsundet”. Lise N. Myhre. (AmS-Småtrykk 46)

Last update November 2022

Back