Society

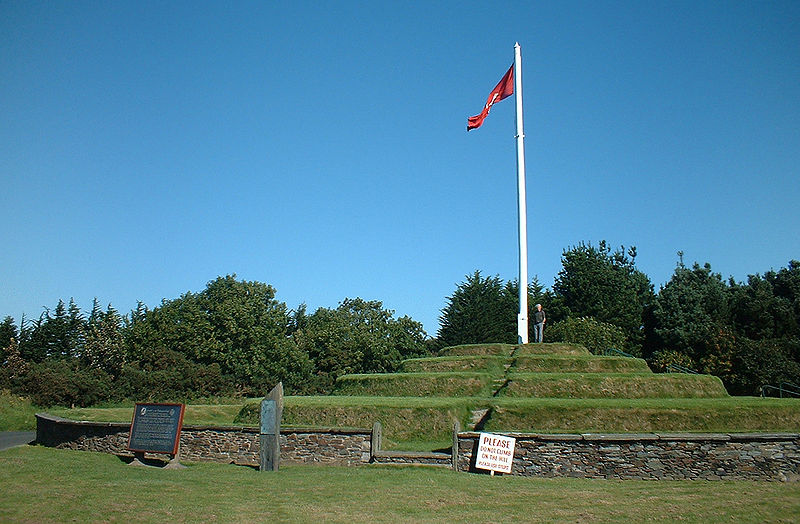

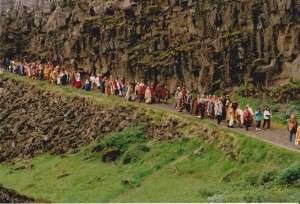

We don’t know exactly where the Gulating was situated, but a memorial is erected at Flolid outside Eivindvik. (Photo: Wikemedia Commons)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

THE LAW

The English word law has an Old Norse origin. (ON lag = law‘)

The laws were memorized and spoken at the Thing by the law-speakers who knew the laws by hearth, until a culture based on written sources was established.

All free man had to respect the law, including the chieftains and the king himself.

THE OLD NORSE LAWS

The old Norwegian laws (called Landscape laws) were local laws which applied in a particular geographic area. These laws are called Gulating Law, Frostating Law, Borgarting Law and Eidsivating Law. These laws applied for every person inside the “law area”. Some of them were written down at the latest in the 11th century. Parts of these laws are still preserved in written form.

The Gulating Law is the oldest book of law in the Nordic countries. The text was written down sometime in the 1000s, but the oldest part dates probably from before 900. Parts of the Gulating Law were used as a model when Ulvljotsloven were written down in Iceland ca. 930. The Gulating Law applied to large parts of western Norway. The law is named after the place Gulen where people from western Norway gathered for their Lagting (superior regional assembly).

Until 1274 the kingdom of Norway had four codes of law, although many of the sections were identical or very similar. Then Magnus Lagabøte had all these laws compiled into one code called Landslova (The National Law) for the entire country.

THE THING – A LEGISLATIVE AND JUDGING ASSAMBLY

The legislation was enforced at the Thing (ON þing), which was the legislative and judical assembly. Compared with contemporary systems, the Norse Thing was a quite democratic institution. The Thing could take political decisions, make new laws and solve disputes. The Thing also functioned as a social meeting place and as an arena to discuss matters of general interest.

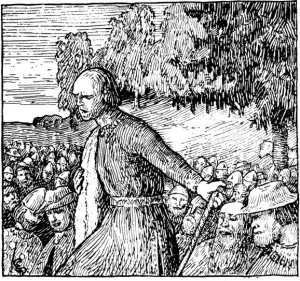

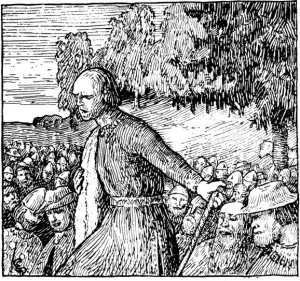

“The Thing in Rogaland”. The king summoned people in Rogaland to the Thing because he wanted them to accept Christianity. It ended with:”..all people present at the Thing were baptized” (Ill. Halfdan Egedius, Saga of Olav Tryggvason)

We do not know when the “System of Things” was established, but the first to write about such a parliament was the Roman historian Tacitus (about 100 AD).

The Althing (ON Alþing ) was a very old institution that existed long before the Viking Age. It was a kind of common assembly for a limited geographical area, for example a village or a rural district. All free men had the duty to meet at the Althing. Women and disabled men could meet if they wanted to. This also had practical reasons. Scattered settlements and large distances meant that someone had to stay home and take care of the farm even though the Althing was set.

Eventually the Lagthing (ON logþing = law-thing), that applied to a larger area, was established. It was then inconvenient that so many should travel over large areas. Instead representatives or “send men”, were elected. This happened probably in the time of Håkon the Good, around 950, and it may have been at this time that women’s “right to vote” disappeared. Nevertheless, a widow could still undertake public functions and meet at the Lagthing instead of her husband.

The actual place where the assambly met was called Thingvoll (ON Þingvǫllr).

Before the Thing was set, a veband (holy band) was laid out at the Thingvoll. This “veband” was a circular area surrounded by a band that distinguished lagretten (the jury) from the other people at the Thing. The area within this bound was sacred. Here prevailed peace and justice.

THE PRINCIPLE OF EQUALITY

Every free man should be treated equally at the Thing. The rule was “one-man one-vote”. In reality the Thing was dominated by the most influential members of the community.

The slaves were not protected by the law. The slaves were looked upon as the owner’s property. The owner could buy and sell a slave, and he could treat his slave as he liked.

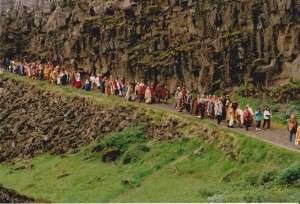

The Althing at Thingvellir in Iceland competes with Tynwald in the Isle of Man and the Lagting in the Faroe Islands to be the world’s oldest continuous parliament body in the world.(Photo Marit S.Vea)

SUMMONS FOR THE THING

The Vikings lived in a brutal time, and they could be violent when they were abroad, but they were heavily punished for violence committed at home. The majority of disputes were solved between the families concerned, but if they could not reach an agreement, the Thing was the final judicial authority.

To summon somebody for the Thing was regarded as a very hostile action. Opponents would therefore try hard to achieve a settlement. A summons could also be a means to force the opponent to agree to conciliation.

The person who was summoned to the Thing, could try to prevent that the summons was conducted according to the rules, for example by escaping or by armed resistance. It was therefore wise of the accuser to have enough manpower to protect himself.

At the Thing the one who accused had to step forward for the judges, take up the contents of the summons and bring forward witnesses and other evidence. Later the accused was allowed to bring forth his defense. Then the judges had the choice to accept the accusation or to reject it.

THE FAMILY AND THE LEGAL SYSTEM

The Vikings had a great sense of justice, but they had no police who could punish criminals. Security was something they found in their families. The whole extended family was responsible if a relation broke the law, therefore the family was important when it came to prevent actions of crime.

The “Thing Hil” in Nord-Trøndelag believed to be the site of the Frostating. The “Thing Hill” is today marked by 13 stones – a big stone in the middle and 12 smaller in a circle around . (Photo Hanne Krogh)

FINES

It was customary to solve disputes by means of fines. The more serious the crime, the higher the fines.

Example: Fines for murder

If a free man was murdered, the family of the criminal would have to pay 189 heads of cattle.

Converted into today’s value:

The killer had to pay 204 800 USD

The killer’s brothers had to pay 74 200 USD

The killer’s uncles had to pay 20 000 USD

The killer’s cousins had to pay 39 600 USD

More distant relatives had to pay 320 – 8 600 USD

The purpose of the fine was to provide for the younger generation of the family who had lost a family member

TO BE OUTLAWED

The most severe sentence passed by the Thing was to banish somebody as “utlegd” (ON utlagi, meaning separated, peace less). Those who were banished were outcasts – they were not protected by the law and stood outside society.

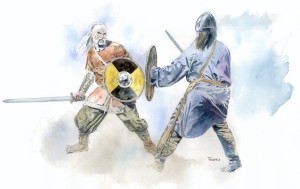

The honour could be restored by holmgang. Those who dueled went out on an island and fought, either to the first drop of blood or to death. There were strict rules for how the duel would take place. The most famous description found is in The Saga of Gunnlaug Ormstunga. Holmgang was abolished by law in 1014. (Illustration Dag Frognes)

None were allowed to have anything to do with an outlawed person. They could not even help him escape from the country. Anyone could kill him. Both society and the plaintiff had a right and duty to take revenge on the outlaws.

Those who were convicted of murder or rape, were often outlawed. This is because the fines for such offenses were so great, that the family of the offender had difficulty paying

HONOUR AND REVENGE

The family was responsible for taking revenge on behalf of other family members. If a person or the family were violated, they had a duty to restore honour.

Honour could be restores through:

– Settlement between the families (Often achieved by fines)

– Conviction at the Thing (Fines or outlaw judgement)

– Through revenge (Blood revenge)

– Through duel (ON holmgang)

“WE ARE ALL EQUAL”

Archaeological evidence shows that there could be great differences between people in the Viking Age. Nevertheless, it appears that the principle of equality was strong. In principle, all free men should also be treated equally by the law. This is also recorded in contemporary foreign sources:

Gunnar from Lidarende was sentenced to outlawry. To save his life he intended to leave Iceland. But when he saw his homestead from the distance, he was so moved by the beauty of it that he changed his mind and decided to remain. This led to Gunnar’s death. (Drawing Andreas Bloch, 1898)

A Norwegian Viking fleet led by Rollo (Gange Rolf) stood by the river Eure. The French king sent an army against them to negotiate. When the French approached the Vikings, one of them asked:

What, ho! brave warriors, what is the name of your lord?” “We have no lord,” replied the Normans, “we are all equal.” (Kilde: Dudo de Sancto Quintino, apud Script. rer. Normani, p. 76., late 1000’s)

RIGSTHULA AND THE ORIGIN OF CLASSES

The old poem Rigstula (ON Rígþula) describes the origin of the different classes. We meet the god Heimdal. He called himself Rig and travelled around on earth like a human. He arrived first at a poor farm, had a child by the farmer’s wife and their son was called trell (slave). “Ground they dunged, and swine they guarded, goats they tended, and turf they dug.”

Later, he arrived at a prosperous farm where the people were well dressed and had good food to eat. Rig had a son – Karl – by the wife on this farm too. “Oxen he ruled, and plows made ready, houses he built, and barns he fashioned, carts he made, and the plow he managed”.

Finally, Rig went to a large and magnificent farm where the farmer was sitting making bows and arrows. His wife was wearing a beautiful, blue dress with a filigree silver brooch and she laid silver dishes on the table. Rig had a son – Jarl – with this farmer’s wife. Rig taught Jarl to be a skilled hunter who could handle weapons well. “Shields he brandished,and bow-strings wound, bows he shot, and shafts he fashioned, arrows he loosened,and lances wielded, horses he rode, and hounds unleashed, swords he handled, and sounds he swam”.

Then Jarl gets sons, and the youngest of jarl’s sons is called Kon-ung (King). The poem goes on to tell what qualities a king must possess. Rig teaches Kon-ung to become a skilled hunter and good with weapons. But the main thing is that Kon-ung has magical powers. He is a rune artist who can heal wounds, comfort, quiet the storms and understand bird-chatter.

But Kon the Young

learned runes to use,

Runes everlasting,

the runes of life;

Soon could he well

the warriors shield,

Dull the swordblade,

and still the seas.

“Heimdal and his nine mothers”. Heimdal who was behind the origin of classes, was himself born of nine mothers on the beach between sea and land. The nine mothers were probably Ran’s nine daugthers (waves). It is not known if he had a father. (Ill. W.G. Collingwood, 1908)

Bird-chatter learned he,

flames could he lessen.,

Minds could quiet,

and sorrows calm;

The might and strength

of twice four men

THE KINGS ELECTED BY THE THING

According to Norse tradition also the kings had to be elected by the Thing. The sagas have many accounts of pretenders to the throne travelling around from Thing to Thing in order to be “chosen as king”. A legacy from their Germanic ancestors?

Tactitus (ca 100 e. Kr.) says this in his volum “Germania”)

“They choose their kings by birth, their generals for merit. These kings have not unlimited or arbitrary power, and the generals do more by example than by authority. If they are energetic, if they are conspicuous, if they fight in the front, they lead because they are admired. (…) In these same councils they also elect the chief magistrates, who administer law in the cantons and the towns.”

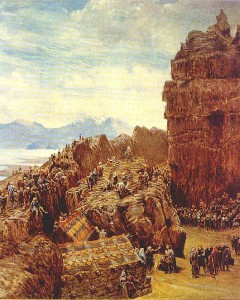

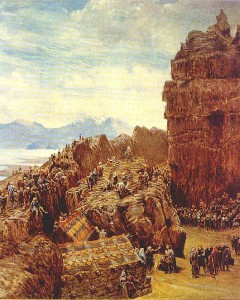

“The Althing on Island meets at Thingwellir.”Adam of Bremen says about the Icelanders in 1070: The people of Iceland have no king – they just have the Law.(Painting W.G. Collingwood, 1870-tallet)

THE VIKING HIERARCY:

Free men Bonded men

Konge (king ) Trell (slave)

Jarl (earl)

Lendmann (highest-ranking follower)

Herse

Hauld (nobleman)

Bonde (farmer)

Løysings sønn (son of a freed slave)

Løysing (freed slave)

FREE MEN

The group “free men” was a motley collection – from the king’s closest followers, to servants. The vast majority of free men were farmers. All free men had the right to bear weapons and to participate at the Thing. Wealth in the form of land ownership was the most important factor in determining free men’s status and importance in relation to one another.

“The farmer” was the backbone of Viking society. There were also other trades and “professions” – often combined with farming – leading to varying social status/wealth.

Priests and priestesses

Magicians

Poets

Smiths

Fishermen

Sailors

Merchants

Craftsmen

Vikings

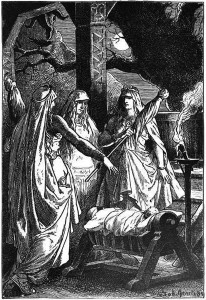

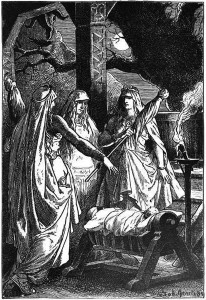

“The Nornes” . When a child is born, the nornes – Urd, Skuld and Verdande – spin its threads of fate. This is done at the foot of Yggdrasil, the tree of life.(Johannes Gehrts (1889).

VIEW OF LIFE

Belief in fate

According to Norse mythology the “nornes” – Urd, Skuld and Verdande – spin the threads of fate for each child that is born. Nobody could avoid his or her fate – whatever you did, your fate would catch up with you. Some think that it was this belief in fate that was the main reason why the Vikings seemed to be fearless in battles.

The “Lay of Hamdir” (ON Hamðismál) says:

With honour we die,

Whether today or tomorrow.

No one survives the judgement of the Nornes.

Honour and revenge

The Vikings had a strong sense of honour. If a person or a family was violated, they had a duty to restore honour. Honour could be restored either through revenge, through conciliation or by conviction at the Thing.

Traditionally revenge was more honourable than conviction at the Thing. This could lead to long feuds and blood revenge. It was the men’s job to take revenge, but the sagas often tell about vindictive women who instigate their male relatives to execute vengeance.

A woman was never in danger of losing her life in a revenge killing, because it was honourless to lay hand on a woman.

It could take some time before the revenge was carried out. An old, Norse proverb says: “Only the slave avenges himself at once, the coward never.”

HÅVAMÅL AND CODES OF CONDUCT

Håvamål (In the Poetic Edda) – “The Tale of Odin” – presents a set of rules for living. Here we can learn about what was important for the Vikings.:

WISDOM

Better weight than wisdom

a traveller can not carry.

It is the poor man’s strength

in a strange place,

worth more than wealth.

Odin sacrificed one of his own eyes to gain wisdom

A GOOD REPUTATION

Cattle die, kinsmen die,

you must die yourself,

One thing I know that never dies;

A dead man’s reputation

TRUE FRIENDSHIP

Far may it be to a false friend

even if he lives next door

A faithful friend may easily be found

even if he is far away.

THE COMPANIONSHIP OF OTHERS

When I was young

and walked alone,

alone I lost my way.

I felt rich when I found company

Man is man’s delight.

Back