Forgotten Royal families

By Marit Synnøve Vea

THE LEGENDARY KING AUGVALD AND HIS DESCENDANTS

Few people today are aware that the Western Norway has preserved a body of legends from the period before the Viking Age. While the oral tradition from several other regions of Norway has become part of a common national heritage after being presented by chroniclers like Sæmund Frode, Agrip, Tjodrek and Snorri to name a few, (*1) the traditions of Western Norway have been primarily preserved in ancient legends, heroic sagas and Old Norse poems.

It may be difficult to determine what is “historically accurate” among the available material. Researchers have therefore chosen to allow such sources to remain untouched as historical material. We must believe, however, that these stories originate from historical facts.

If we remove the supernatural element, combine a variety of sources and compare them with archaeological evidence then this part of our cultural heritage should be able to provide new historical knowledge. However, it is more exciting to retain the magical overtones, as the stories then present a clearer perspective of our ancestors’ immaterial culture and of their conception of the world.

“HISTORIA RERUM NORVEGICARUM…”.

The Islandic historian Tormod Torfæus wrote Historia rerum Norvegicarum, the first comprehensive presentation of Norwegian history since Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla. Torfæus had at his disposal a number of medieval Old Norse saga manuscripts, and he was a pioneer in using these as source material.

In the preface of Historia rerum Norvegicarum, Torfæus says:

One should not immediately assume that that which does not conform to the customs and fashions of our own century are necessarily untrue. Hidden truths can frequently be found within the camouflage of a fable. Truths are often openly mixed with falsehood. Sometimes it is easy to determine one from the other, while at other times it is almost impossible even with great effort. (*1)

Torfæus continues:

There are many examples to choose from, but I shall cite just one. The legends of King Half Hero and Olav Tryggvason tell of two such stones that were raised as a memorial to Ogvald from Rogaland and the cow. He worshipped this cow while alive and decreed that it should be placed in the burial mound together with him when they died. One of these stones can be seen on the island of Karmøy, where I reside, at the Avaldsnes vicarage and there is nothing that is not in accordance with the old story. This provides an undoubted credibility; not just to the existence of this Ogvald, but to the things that have been read about him in the recently mentioned stories. (*1)

In this article I have decided to take a closer look at the legendary King Augvald or Ogvaldr and his descendants, inspired by Per Hærnes and Arnfrid Opedal, with whom I have been allowed to discuss the material and who have both generously shared their knowledge. They have both discussed this matter in the books “Karmøys Historie”, bind 1 (’The History of Karmøy,” vol. 1) (Hærnes) and “De glemte skipsgravene” (“The Forgotten Ship Burials”) (Opedal). We can also hope that others immerse themselves in these stories and become acquainted with the people who were once discussed around crackling bonfires and in the light of the silent peat-fires by the fireplace.

THE FORCES OF NATURE PERSONIFIED

All of the Norse royal families had to justify their right to rule. Among the methods used to achieve this, was the tracing of their bloodlines back to divine creatures. The Ynglinge bloodline is believed to originate from the Swedish Yngve Frey of the Vanir family. The Lejre Kings in Denmark are descendants of Odin’s son, Skjold of the Æsir Family, the little boy who came bobbing onto the Danish beaches in a boat without oars.

The West-Nordic royal families, to which Augvald belonged, could trace their ancestry back to Fornjot from the jotun lineage, the oldest and most feared of all the divine creatures. As the name suggests, Fjornot is most likely another name for the ancient giant Ymir. (2*) Audhumla, the primeval cow, was created together with Ymir when the world was originally formed in a meeting of fire and ice at Ginnungagap, with Audhumla’s life-giving milk providing nourishment for Ymir.

The giants were created from the hermaphrodite Ymir/Yme, while the primeval cow Audhumla brought to life the creature Bure by licking salt from the rime ice. Bure’s son Bor and the female giant Bestla produced three sons, Odin, Vilje and Ve, the first of the Norse gods. Odin and his two brothers later killed Ymir and from his body they created heaven, the sea and the earth. They later discovered two logs lying on a beach and from these they gave life to the first two humans on earth; Ask and Embla.

The ancient giant can also be found in the myth depicting the origin of the West-Nordic kings. Here he bears the name Fornjot, the northernmost king, at the end of the world. Fornjot was father to Kåre (the wind), Loge (the fire) and Ægir (the sea). Kåre begat Frost who sired a son, Snø (the snow). Snow was the father of Thorre (the frost). All of these are personifications of natural forces. Thorre fathered two sons; Nor and Gor and a daughter, Goe.

GEOGRAPHICALLY DERIVED REGAL NAMES

Following the abduction of Goe by a giant, her brothers left home in search of her. Gor travelled by sea while Nor waited for the snow to fall before setting off on skis over the mountains towards the north, until he reached the point where the rivers ran to the west.

Nor followed the rivers to the coast where he met up with his brother Gor. The brothers discovered that the land had previously been inhabited, though this did not prevent them from claiming it as their own. They eventually found Goe and her captor, the giant Rolf. Conflict broke out but this was later replaced by peace as Goe married Rolf and Nor took the hand of the giant’s sister. All Norwegians are descended from these two, and the name Norway, according to the myth, means Nor’s kingdom.

Nor had a son, Gard Agde; a name which some believe is attributed to the Agder counties, which is thought to be his place of origin. However, the plural form of Agder at this time simply meant ‘coastal region’. (2*) The name “Gard Agde” can translate to read “The Coast Guardian”. Gard Agde had many sons whose names could be connected to individual counties. Among them his son Rugalf who had a son named Rognvald. These became kings in the county of Rogaland. Rognvald was the father of Augvald, of whom Avaldsnes has taken its name.

We can see in the genealogical line originating from Nor that the individuals have ceased to be divine. They have become human. The history covering the period from Nor through to Rognvald also appears much newer than the original narrative, which dealt with the creation of the earth and the forces of nature. It seems, in this last part, as though someone has attempted to make a connection of lineage between divine beings and the ancient royal families. These lines have been found in geographic locations, believed to have been named after possible kings. What then of the king we call Augvald?

AUGVALD

The Norse name for Augvald was Ogvaldr, of which the latter part, valdr, means “one who rules”. The first part of his name is thought to derive from the West-Nordic , meaning unrest and fear. Ogvaldr can therefore be translated as “the ruler held in awe by the people”. The first part of this name may also have its origin in the Old Norwegian ogn, meaning dangerous/frightening and is often used in association with water, as in Ognøy and in the river Ogn. However, it is equally possible that Ogvaldr is connected to a geographic area and that the first part stems from ogð (Indo-European *ak).

Ogð originally meant sharp or protruding, but eventually the word came to represent the coastal countryside. According to P.A. Munch, the plural form of Agder was known as “stretches of coastline” and Agdenes in Trondheim could be interpreted as “land protruding into the sea”. Based on this translation, Og(ð)valdr could mean “The Ruler of the Coast”.

Ogvaldr, or Augvald, is mentioned in The Flatey Book (Flateyjarbok), the Book of Settlement (Landnåmabok) and in the Saga of Half & His Heroes. Snorri Sturlason writes of Augvald in Olav Tryggvason’s Saga and he is also referred to in the manuscripts of Odd Munk. In addition to these we can draw on the Karmøy legend of King Augvald and King Ferking. Augvald is also to be found in the Avaldsnes parish register.

THE LEGEND OF AUGVALD

Augvald is first and foremost known through Snorri’s account in the Saga of King Olav Tryggvason while the older Latin manuscript of Odd Munk, Olav’s Saga, provides additional details. Let us take a look at a short résumé.

One year, around Christmas, Olav Tryggvason was at Avaldsnes when he received a visit from a one-eyed, old man with many a tale to tell. The old man knew also of a King Augvald, who had worshipped a cow and who had given his name to Avaldsnes. It wasn’t until the one-eyed man disappeared early the next morning that Olav Tryggvason realised it had in fact been Odin who had visited Avaldsnes and told of King Augvald. Olav hurried to the burial mounds of which the old man had spoken. In one of the mounds he found human remains and in the other he found the remains of a cow.

According to legend, King Augvald lived during the Migration Period; approximately 600 AD, though Torfæus places him much earlier in the 3rd century. Both the Saga of Half and his Heroes and the Avaldsnes parish register describe how he was originally only king on the mainland but that he managed to claim the The Land of the Holmrygr, as a result of his many successful battles at sea. After achieving this he decided to settle down at the place he considered to suit his needs best. This place has since been known as Avaldsnes.

King Augvald was a battle-hungry man who often raided foreign countries, winning both wealth and honour. He had a sacred cow whom he worshipped and whom he took with him wherever he travelled; drinking milk from the cow to give him strength and vitality. Augvald had a son named Jøsur and, according to the Karmøy legend, several daughters, of which two were female warriors, shield-maidens; known to accompany their father at all of his battles.

A number of people have been accredited with taking King Augvald’s life. Tormod Torfæus believes that several warriors or kings must have fought with Augvald, yet no author has succeeded in putting a name to them all. Snorre proclaims Varin to be the assassin while The Flatey Book believes he was killed by Dixin. The Saga of Half and his Heroes tells of Augvald being murdered by “Hæklings men”, though this could just as easily mean caped men or warriors.

It was long ago

they laid a course

here in their hundreds,

Haekling’s men,

sailed the salty

sea-trouts’ track.

That’s when they crowned me

king of this mound.” (Translation: Peter Tunstall, 2005)

The Karmøy legend speaks of the many battles between King Augvald and King Ferking/Kverke from the Westside of Karmøy. Ultimately both King Augvald and his sacred cow were killed in battle at Ferkingstad. Upon witnessing this, the shield-maidens threw themselves in the nearby river and drowned. King Augvald and his cow were taken to Avaldsnes and laid to rest in burial mounds, while his daughters were buried at Stavasletta, where memorial stones were placed to mark their graves.

YMIR AND AUGVALD

The history of Augvald is of a very ancient quality with a direct connection to the myth of Ymir and the creation of the world. Historical sources draw a parallel between Augvald, Ymir and a sacred cow, where both have gained vitality from drinking milk of a bovine creature. The relationship between king and cow can also be found in the story of Sigurd Fåvnesbane in which we meet the Swedish king Eystein, who was known to worship a cow.

We have reason to believe that the myths of origin were also expressed in ritual events. In the book “De glemte skipsgravene”, telling about the two rich ship burials at Avaldsnes, Arnfrid Opedal explores the ship burials as ritualised myths. She also suggests that the Storhaug ship burial may be an interpretation of the myth of origin surrounding Augvald’s bloodline. (3*)

Although there is no archaeological evidence to support the existence of the legendary Augvald figure, we can at least ask the question whether the rulers of Avaldsnes also had certain ritual responsibilities.

AUGVALD/ODIN

There is also a connection between Augvald and Odin, who killed Ymir and created the world from the giant’s body. Odin himself is responsible for sharing the story of King Augvald and his sacred cow with King Olav Tryggvason. This happened at Christmas; a time traditionally associated with Odin, or Jolnir (jol/jul is the Norwegian name for Christmas) as he is also known. It was a normal belief that those laid to rest in the burial mounds erected on their own estate would rise from these mounds around Christmas time. In this case it is not Augvald who rises from the dead, but Odin himself. Or perhaps it was Augvald after all? (4*)

In rites, Odin (in the guise of Augvald?) may have been looked upon as the masculine force/primeval ox, in contrast with the feminine force/primeval cow. A horned figure can be found over the left eyebrow of the Sutton Hoo helmet. This helmet was probably used in ceremonies and is spoken of as “a helmet like that worn by Odin”. A bronze poster from the 6th century, Torslund at Øland, shows two warriors engaged in a ritual dance. One of these warriors has a horned helmet while the other wears the mask of a wolf. It is believed that this poster depicts a ritual relating to Odin. (5*)

The primeval cow stands in contrast to the primeval ox/Odin, and symbolises the feminine part of the entirety. The primeval cow could be the ritual expression for feminine fertility in its widest possible sense. Odin was the husband of Frigg. It is also most likely that he is the Od to whom Frøya was married. It is believed that both Freya and Frigg grew from an original goddess of the earth.

The earth goddess was divided into several figures in which Frigg was given the maternal values while Freya inherited the erotic qualities. Through Freya’s role as the goddess of death (she shares half of the fatalities from the battlefield with Odin) we can see the course of nature and the connection between birth, death and re-birth. There are indications here that may form part of rites connected to Augvald and his cow worshipping.

ODIN AND AUGVALD’S SHIELD-MAIDEN (VALKYRIES)

Odin is associated with valkyries. Augvald, if we are to believe the ancient Karmøy legend,had two daughters who were shield-maidens. These female warriors or valkyries were traditionally also a form of “goddesses of destiny”, closely related to the Norse nornes. The word valkyrie means “chooser of the slain”, and valkyries were sent by Odin to select the fallen warriors who were to be allowed entry to Valhalla as heroes. Thus; shield-maidens or valkyries were also known as “Odin’s maidens”. Some of these were heavenly valkyries while others were half terrestrial/half heavenly; living for a while on earth as mortal beings before entering Valhalla as female heroes. Norse legends also talk about ordinary mortal women who dressed up and fought like men.

AUGVALD; A HISTORICAL PERSON OR A CULT FIGURE?

It may be true that a genuine King Augvald once lived at Avaldsnes. It may also be true that he really did have two daughters who fought side-by-side with their father in all his many battles. It is equally probable that Augvald was the name given to whoever may have ruled over this protruding part of the coastline, controlling the maritime traffic in and out of the strait Karmsund; a person who served both political and ritual functions.

Perhaps one of these “Augvalds” was so remarkable that the story of Augvald has been formed around him. Or perhaps the story is a combination of numerous incidents from the lives and times of several “Augvalds”, “rulers of the coast”. Then what so of the sacred cow and the shiled-maidens? These may also have been real, living creatures, though they could just as likely have been part of a process of worship, used by people to come in closer contact with the gods.

AUGVALD’S KINGDOM

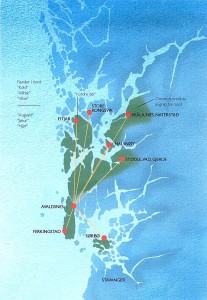

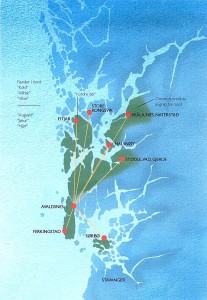

Comparison between the kingdom that the Storhaug prince ruled over in the 700’s and the sources that tell of “Augvald Kingdom”, gives a surprising coincidence.

Red dots mark sites connected with the realm of 700s.Green colour mark areas mentioned in connection with king Augvald according to “the Archive for the Department of Education and Information” by Dr. P. Hansen.

(Map from: ”Kongemakt og kongerike. Gravritualer og Avaldsnes-områdets politiske rolle 600 – 100″. A. Opedal, Oslo 2010)

AUGVALD’S KINGDOM IN ROGALAND AND HORDALAND

The ancient sources tell of how Augvald, a non-local, settled down at Avaldsnes on the island of Kormt, the largest island in the Ryfylke region. A relatively unknown text, “the Archive for the Department of Education and Information” by Dr. P. Hansen, written around 1800 AD”, describes the geographic extent of Augvald’s kingdom. Dr. Hansen chooses not to name his sources, though he does refer to Tormod Torfæus in areas of his text. He also credits pastor Krogh from Skudenes for the useful historical and topographical information he provided. It is clear from the tone of the text that a large proportion of his material is drawn from the legend of Halv. Dr. Hansen writes:

He (Augvald) has since expanded his dominion over the remainder of mainland Rogaland, after having banished Karmøy’s and the other islands rulers from their estates, as if it were his desire to continually be either at war or on raiding expeditions. On both sides of the island as well as his place of residence, he controlled important outlets to the North Sea, such as: Hinderager-Vaagen and Vikingstad-Vaagen, outside which the Faroes and many other islands lie. (…)

Mosterøen and Storøen also belonged to Augvald’s kingdom, as did the greater part of Fieldberg, namely Vige or Vide Sogn, Aulands Sogn, Æthne, Vallerstrand and Sveens Sogne. Gundvold, who was responsible for the upbringing of his son Josur, was named Earl of the northern regions of these Hordaland provinces.

Dr. Hansen recounts the narrative from the Saga of Half and His Heroes of how Jøsur Augvaldson was slain by Vikar while attending a banquet in Kvinnherrad …

… and all of the males who had taken to arms for Jøsur were killed; and since none other than the women of this bitter enemy were spared, this part of the country was given the name Qvina, or Qvindherred. Vikar was later deprived of these areas by Jøsur’s son Hior who inherited the throne of Rogaland after the death of his father. Hior was a wise and powerful sovereign, praised for his work in reuniting Hordaland and Rogaland.

CAN WE TRACE AUGVALD’S KINGDOM THROUGH ARCHAEOLOGY?

Arfrid Opedal has looked at the extent of the 8th century kingdom in Rogaland and Hordaland that was ruled by the king buried in the Storhaug ship. She has compared this area with the extent of king Augvald’s kingdom, as it is described in written sources. She finds a remarkable coincidence. According to written sources, this is also the area that royal families in Western Norway fight over in the generations to come after Augvald.

HALF – THE NOBLE HERO

The Saga of Half & his Heroes tells of the young Half, aged 12, already prepared to partake in Viking raiding missions. He had soon gathered 60 of the finest warriors from 11 counties with whom he carried out raiding missions in Austerveg for a period of 18 years.

It has been said of Half and his army of warriors that they never once lowered their sail or searched for a port, choosing rather to lie at the outermost coastal point. Once, when a huge storm washed over them at sea, they fought each other for the right to jump overboard first as they cried: “Stråløst er det framfor stokkene”. Meaning ”those who jump over the shipside, do not have to face a sickbed”

Half and his warriors would not dress their wounds until at least a day had passed and they used short, single-edged Saxon swords to bring them closer to the enemy. They had a reputation for never attacking women or children. Half reputedly demanded that his men should treat women with respect, and “marry them with gifts”. Half was the king of both Rogaland and Hordaland. Once, upon returning home to his kingdom, he found that his stepfather, Åsmund, had proclaimed himself king of Hordaland in his absence. In an act of treachery, Åsmund set fire to the hall where Half and his men were banqueting. The fire cost Half his life.

Innstein, one of Halv’s confidants, died together with his king whilst saying the following verses:

I’ve been at sea

eighteen summers,

a bold boss I served,

stained shaft with blood.

Another lord

I’ll never find

more gallant in war,

nor grow old now.

So here Innstein

sinks to the ground,

lays himself down

by his leader’s head.

In latter times

at the telling of sagas,

they’ll hear of how

King Half died laughing.” (Translation: Peter Tunstall, 2005)

Innstein was the father of Ottar, the main characters in the poem Hyndluljod. In this poem Freja takes her favourite Ottar with her on a journey to the giant Hyndla who recites the list of Ottar’s wonderful ancestry while constantly repeating the words, “These are your ancestors Ottar”.

AUGVALD’S GENEALOGICAL CHART

In the ancient legends the history of the counties Rogaland, Hordaland and to an extent Agder, is woven together. Using Augvald’s genealogical chart as a starting point we can research the chronological order of some of the characters that feature in the legends.

he dates suggested are estimates based on the knowledge of Geirmund and Håmund Heljarskinn’s departure for Iceland following the battle of Hafrsfjord, ca. 870 AD. The Book of Settlement (Landnåmabok) claims that Geirmund was an old man before he set off. I have placed his age at 40 and the date of his journey around the year 880. Each generation is calculated on average as covering 30 years, though it may be more accurate to assume a gap of 25 years between each generation.

FAMILY TREE OF AUGVALD, HIS DESCENDANTS AND ACCOSIATED

|

HORDALAND/ROGALAND

|

NORD MØRE

|

ROGALAND/AGDER

|

HORDALAND

|

(ROGALAND)

|

|

Augvald

|

Hild

|

Vikar

|

Innstein

|

|

|

Fornjot

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Ægir/ Loge/) Kåre

|

|

600

|

Frost

Snø

Thorre

Nor

Gard Agde

Rugalf

Rognvald

Augvald

|

Grjotgard

Salgard

Grjotgard

|

Harald Agdekonge

|

|

|

|

630

|

Jøsur (1)

|

Sølve

|

Vikar (5)

|

Sæfare

|

Klypp

|

|

660

|

Hjør

|

Høgne i Njardø

|

Vatnar

|

Ulv

|

Kjetil

|

|

690

|

Hjørleiv married to Hild

|

Snall/Hjall

|

Alv

|

Friund

|

|

720

|

Ublaud

|

Halv (og Hjørolv)

|

————-

|

Innstein married to Ledis

|

|

750

|

Utrygg

|

Hjør

|

————-

|

Ottar (7)

|

|

780

|

Høgne

|

Flein (3)

|

————-

|

|

810

|

Ulf (4)

|

Hjør Fleinson (3)

|

———–/Orlyg

|

|

840

|

|

Geirmund Heljarskinn (2)

|

Tormod(6)/Valtjof

|

COMMENTS ON THE GENEALOGY

1. The Flatey Book (Flateyjarbok) has singled out Hord as the forefather of the Hordaland royal bloodline and declares Jøsur as his son. The Saga of Half and his Heroes claims Jøsur to be the son of Augvald. P.A. Munch believes The Saga of Half and his Heroes to be correct: “The Saga of Half and his Heroes states unequivocally that Jøsur is a son of Augvald, king of Rogaland, which must correspond with the legend’s true form”.

Torfæus is also categorically clear that The Flatey Book is inaccurate and that Jøsur was the son of Augvald. He moves Hord further back in time, claiming him to be the father of Rugalf and that Gard Agde is therefore not Rugalf’s father, but his grandfather.

2. The skald Brage the Elder is accredited with writing a poem of Geirmund and Håmund. Brage’s grandson, according to The Book of Settlement, was Tore Herse Roaldsson; Eirik Blood-axe’s foster father.

3. Flein Hjørson and Hjør Fleinson are not included in old genealogies that appears thus: Half – Hjør Halvson – Geirmund and Håmund Heljarskinn. P.A. Munch,suggests that two generations can have been mislaid here involving the two “Hjørs”. He believes these lost generations can be found in another part of The Book of Settlement (of Iceland) (Landnamabok):

Hjør Halfson married to Hagny, daughter of Hake Håmundson (Half’s saga)

Flein Hjørson (skald) married to a daughter of the Danish king Eystein (Book of Settlement)

Hjør Fleinson married to Ljufvina, princess from Bjarmeland (Book of Settlement).

4. The Book of Settlement includes Ulf Skjalge as an early settler. It would appear that a generation has been skipped between Utrygg Ublaudson and Ulf Skjalge. The Book of Settlement calculates the lineage thus: Utrygg – Ublaud – Høgne.

5. The Saga of Half and his Heroes and The Flatey Book both claim Alrek Hordakonge to be Vikar’s father. The Gautrek Saga and The Book of Settlement however, maintain the father to be Harald Agdekonge. P.A. Munch feels the latter to be closer to the truth and follows the assertion that Vikar is the son of Harald. He also doubt the very existence of Alrek Hordakonge. The Saga of Half, which Munch otherwise considers being the most trustworthy, concentrates on the lineage of Half and mentions Vikar only in passing.

6. The Book of Settlement shows settler Thormod Skafte to be the fifth generation descendant of Snjall. Orlyg Gamle and his son Valtjoft left together for Iceland and are fourth and fifth generation descendants of Hjall respectively.

7. Innstein is the father of Ottar who learns of his own genealogy and the genealogy of others through the poem Hyndluljod. The brothers Innstein and Utstein were among Half’s warriors along with their cousins Rok the Black and Rok the White.

|

Berserken Hromund (Håmund?)

|

| Håmund herse (brother of) |

Gunnlad (sister of) |

Hake Hromundson |

| Rok the Black and Rok the White |

Utstein and Innstein |

The Sea king Håmund |

| |

|

Hake Håmundson |

| |

|

Hagny (married to Hjør Halfson) |

MIXTURE OR HISTORICAL FABRICATION?

The lineage above is an attempt at systemizing some of the information of Rygish, Hordish and Egdish royal lineage based on details gleaned from some of the oldest available literature. We can create several ancient scenarios of what actually happened from the information at hand. It is, however, difficult to determine what is historically accurate. Several factors contribute to this ambiguity,among them are:

– that the events occurred long before the story was told

– the story or stories could be pure fabrication

– differing versions can be equally “true” due to the same person appearing under different (nick)names.

– the events could be purposely muddied in order to hide unfortunate situations

– deliberate attempt to falsify history in which the “victor” erases the loser from the history books, tying his own family tree into the ruling genealogy of a particular area.

In the body of legends concerning the west Norwegian royal families we encounter, among the generations following Augvald, two warring “royal families” apparently fighting over the same area: “Vikar’s family” with their origins in Agder and Rogaland and “Jøsur’s family” with their roots in Rogaland and Hordaland. The story of both these “royal families” can be found primarily in The Saga of Half and his Heroes and in The Saga of Gautrek.

There are contradicting theories concerning the fatherhood of Jøsur and of Vikar, and there is a certain amount of uncertainty regarding the borders of the “kingdoms” of Rogaland, Agder and Hordaland. The Saga of Half and his Heroes claims Jøsur to be the son of Augvald while The Flatey Book names Hord, of whom Hordaland took its name, to be the father of Jøsur.

Torfæus, who categorically repudiates that Hord is Jøsur’s father, draws on his studies of the genealogy of Hord when claiming that he is indeed the father of Rugalf, of whom Rogaland was named. If Torfæus is right, then this indicates a belief that the royal family of Rogaland stem originally from Hordaland, or that Hordaland and Rogaland were once united as a single “kingdom”. It is this kingdom, according to the ancient legends, that the warring families of Rogaland and Hordaland were later to fight over.

HARALD AGDEKONGE IS LOST TO HISTORY

The Saga of Half and his Heroes tells that Vikar killed Jøsur, son of Augvald. Both this saga and The Flatey Book claim Vikar to be the son of a certain Alrek of Hordaland. The Flatey Book even allows the Agder lineage, through Trym, to die out after just a few generations. However, in The Saga of Gautrek and in The Book of Settlement we learn that Vikar’s father was the mighty Harald Agdekonge.

Harald Agdekonge, according to The Saga of Gautrek, was killed by King Hertjov of Hordaland who declared the kingdom his own and took Harald’s son Vikar and Vikar’s foster brother Starkad with him to Hordaland. Vikar avenged his father’s death by slaying Hertjov and became king of Agder, Jæren, Hordaland, Hardanger and “the entire kingdom taken by Hertjov”.

Vikar was later to acquire Telemark and Oppland, though he was later killed by his friend Starkad. We meet the Rygish (2*) Starkad later as a warrior and skald serving under the Danish kings Frode Mikellati (Frode den Frøkne) and Ole the Bold (Aale den Frøkne).

The Saga of Gautrek mentions two of Vikar’s sons by name; Harald, who was to inherit the kingdom after his father’s death, and Neri (Nere)who was to become king of Oppland and Telemark.

The Saga of Gautrek, which concentrates mainly on Vikar, provides us with the most likely version of Vikar’s parentage. Alrek of Hordaland would appear to be a fictive person named after the mountain range, Ulriken. (2*). It seems also unlikely that Vikar, who later became king of “his father’s old kingdom”, should be the son of a Hordish king named Alrek.

The motive for erasing Harald Agdekonge from the history books requires further investigation. He was, after all, the king The Saga of Gautrek honoured with uniting Hordaland, Rogaland and Agder to one great kingdom. Do we detect a hint of historical manipulation, where the legendary Vikar (grandfather of, among others, Gyda, wife of Harald Fairhair) is moved into a Hordish/Rygish dynasty and is given divine forefathers? Harald Agdekonge was denied such an honour and not even The Saga of Gautrek mentions his ancestors.

VIKAR – A SACRIFICE TO ODIN

The Saga of Half and his Heroes tells of a prophecy in which Vikar was promised to Odin while still in his mother’s womb. The prophecy is fulfilled in The Saga of Gautrek in which Vikar, on his way from Agder to Hordaland, is treacherously slain by his best friend, the legendary Starkad. This murder is carried out at the request of Odin.

Here we can see, also in The Saga of Gautrek, that Hordaland was part of Vikar’s domain when it is stated that: Starkad was strongly hated by the people for this action, and for this he was banished from Hordaland. Overwhelmed by regret, Starkad later composed the ode “Vikarsbolken” to depict the events.

Since then I have been lost,

wandering unknown paths

away from Hordaland,

my mind mournful,

missing my king,

my soul filled with sorrow. (Translation M.S Vea)

We therefore have the situation where Vikar, king of Agder and Rogaland, claims the life of Jøsur, king of Rogaland and Hordaland. We are told that the people of Hordaland react strongly to this episode after the death of Vikar. We find similar instances among Vikar and Jøsur’s heirs who alternately and simultaneously were known as kings of Agder, Rogaland and Hordaland. It is precisely this kind of contradiction in the ancient manuscripts that have lead researchers to consider these ancient legends unfit for use as historical sources.

CONFLICT BETWEEN ROYAL FAMILIES OR PRETENDERS TO THE THRONE?

Some meaning can be given to this if we assume that Jøsur, Vikar and their heirs shared the same ancestry and had the same “allodial rights” to the aforementioned areas. We may ask the questions: Are Augvald and Harald Agdekonge the same person? Can Vikar and Jøsur have the same origin? Were they nephews who both felt they could lay claim to certain areas in Hordaland, Rogaland and Agder? Was this fight for control of these areas in reality a fight between brothers, their heirs and their followers, similar to that which we later see in the power struggles during the Viking Age and the civil war era.

From the Sagas of the Norwegian Kings we are familiar with the system of banqueting; kings toured a variety of estates, taking up temporary residence. Asgaut Steinnes believes that parts of south-western Norway practiced an unusual form of taxation known as utskyld, a system that was operative before the unification of Norway. (7*) We can assume that the smaller kings, in the centuries leading up to the Viking Age, had several estates spread over a greater area. It is therefore unlikely that a royal family owned only one specific allodium in a particular area. We must believe, however, that to have control of Avaldsnes was necessary for those wishing to proclaim themselves “Rulers of the Coast”.

AUGVALD’S NES – THE COASTAL FORTRESS

We should perhaps look upon Avaldsnes as the single most strategically significant location in the area; often fiercely fought over by kings and pretenders to the throne alike. In which case we need not consider a Karmøy or Avaldsnes lineage, which expanded and took control of the surrounding areas. On the contrary, Avaldsnes may have been a site that was conquered by a variety of opponents. Avaldsnes became the coastal fortress or “West Norway’s Lejre” as professor Magnus Olsen calls it. Those who gained control of Avaldsnes also had control of the coast. He was “Ogvaldr” and he intended to maintain his position by striking up alliances along the coast by means of marriage and gifts.

Avaldsnes, and the adjacent Strait of Karmsund, has been known throughout history as an important mythical site for seats of power, and is closely tied to the establishment of dynasties and the royal lineage originating from the gods. We see this through the myths of origin, the interpretation of the ship burials as ritualised myths, Harald Fairhair’s burial by the Strait of Karmsund and Olav Tryggvason’s exhumation of the burial mounds at Avaldsnes; intended perhaps, to prove his (doubtful) relationship with Harald Fairhair.

The conflict of which the ancient legends speak may also mirror a battle between political and religious power. In the book Karmøy’s History, Per Hernæs describes the Germanic form of government in which a person of royal blood would be chosen by the council to rule the kingdom in times of peace. The same council would choose a temporary ruler during wartime; relinquishing power when peace was reinstated. There is reason to believe that several of these wartime kings were reluctant to hand over the throne. (8*) This could result in two “royal families” operating in the same area. Perhaps the warring sovereign attempted to strengthen his position by carrying out ritual tasks?

We are told of a Hordish/Rygish dynasty and of an Egdish/Rygish dynasty in the ancient legends. The following questions need to be addressed; which areas of Hordaland, Rogaland and Agder are we referring to here and where do such “kings” as Harald Agdekonge and Hjetjov of Hordaland fit in? Where were the boundaries of the small kingdoms and where were they most significant? Can we be sure that the areas of which we speak were within the confines of the county borders as we know them today? Can new information be gleaned from the comparison of archaeological finds and the information contained in ancient literature? Can information of the utskyld tax system and the banquets thrown in honour of the visiting kings help to localise the small kingdoms and clarify their possible involvement in larger kingdoms?

KING HALF AND HIS DESCENDANTS.

There appears to be full agreement in even the oldest literature regarding the royal lineage and the royal titles stretching from Jøsur to Half. They are all described as kings of Rogaland and Hordaland. Doubts around the lineage are first raised with Hjør Halfson, ca. 750 AD. Geirmund and Håmund Heljarskinn, among the most prominent original settlers in Iceland, are described as Hjør’s sons, however, P.A. Munch claims these must have been Hjør Halfson’s grandchildren.

We therefore have a Hjør who is the son of Half, and a Hjør who is the father of Geirmund and Håmund Heljarskinn. The sources state that Hjør’s sons are Rogalenders, and Geirmund Heljarskinn is described as a “warrior king” with a kingdom in Rogaland. Despite this, the sources do not let them possess royal titles equal to their predecessors

The uncertainties begin with Half’s death. So who really was this King Half whom we know through the Saga of Half and his Heroes?

The legend tells of how Half and his men travelled around Austerveg, fighting with short, single-edged Saxon swords; a fact which would tie in with the archaeological finds dating from the Merovingian Age. Half’s parents were Hjørleiv “the womanizer”, king of Rogaland and Hordaland and Hild the Slender from North Møre. Could this be a sign of alliance building along the coast? The legend tells us that Half died aged 30. According to our genealogical chart, Halv lived from 720 – 750 AD. If we assume a period of 25 years between each generation, Halv would have lived between 740 – 770 AD; a 20-year gap between generations would place his life span at 760 – 790 AD.

THE SHIP BURIALS IN GRØNHAUG – STORHAUG AND THE OSEBERG SHIP

Two burial ships, Grønhaug and Storhaug, have been found in the area of Avaldsnes. The Storhaug ship burial also contained a smaller boat. Tree-ring dating carried out by Frans-Arne Stylegar and Niels Bonde, published in 2009, has proved that the Oseberg ship originates from the same area as the Grønhaug ship, the Storhaug ship and the Storhaug boat at Avaldsnes (*9). The Oseberg ship was built around 820, while the Oseberg burial took place ca 834.

For the first time we have archaeological evidence of close contact between the House of Yngling in Vestfold and the Avaldsnes kings of Western Norway. Stylegar suggests that the Oseberg ship might have ended up in Vestfold because a princess from the Avaldsnes area brought it with her as a dowry when she was married off to a king of Vestfold.

Through tree-ring dating Stylegar and Bonde has dated the timber of the Grønhaug ship to ca 780. The burial, however, took place sometimes between 790 – 795. The Storhaug ship burial is dated to 779. The Storhaug site revealed the remains of a sovereign laid to rest in a large Nordic ship, though the equipment he was buried with proves close connections with the Carolingians.

WHO WAS BURIED IN THE SHIP BURIALS OF STORHAUG AND GRØNHAUG?

Ship burials are aristocratic burials. Speculation as to the identity of the persons buried in the ship burials in Grønhaug and Storhaug offers several likely candidates. Based on the presentation of the genealogical chart, with a space of 30 years between generations, Half lived from 720 – 750 AD (alternatively, somewhere between the years 720 – 790). Half’s father, Hjørleiv “the womanizer”, king of Rogaland and Hordaland, lived from 690 until his death, while on a raiding mission, in 740 AD. Half’s grandfather, Hjør Jøsurson, king of Rogaland and Hordaland lived from ca. 660 – 700 AD and was entombed in a burial mound in Rogaland.

The same genealogical chart provides the names of three kings ruling in Rogaland/Hordaland during the period 690 – 790 AD, namely Hjør, Hjørleiv and Halv. One of these might have been buried at Storhaug or Grønhaug.

By adjusting the chart to a 20-year gap between generations, as Arnfrid Opedal has, increases the likelihood of the sovereign buried in Storhaug or Grønhaug being none other than the founder of the dynasty, Augvald. (3*)

“HIDDEN TRUTHS CAN FREQUENTLY BE FOUND WITHIN THE CAMOUFLAGE OF A FABLE…”.

History changes according to new knowledge and new research methods. What we to day call “history”, is our own times interpretation of the past. We may speculate all we will over the identity of the person buried in the Storhaugship, the Grønhaug ship or the Oseberg ship, but we will never really know the truth.

The three first volumes of the translation of the Icelander Tormod Torfæus’ historical work Historia rerum Norvegicarum was published in 2008. His work shed new light upon this obscure legendary period in which we find Augvald’s descendants in Rogaland and Hordaland (and Vest Agder?), as well as shedding light upon the genealogy and events from other areas of the country. Through his work we can all share in these fantastic stories.

Thus; we give the last word to Tormod Torfæus: One should not immediately assume that that which does not conform to the customs and fashions of our own century are necessarily untrue. Hidden truths can frequently be found within the camouflage of a fable.

———–

This is an article composed of excerpts from two articles I have written before:

– Den fabelaktige Augvald og hans ætt: (Et hus med mange rom. Vennebok for Bjørn Myhre, AmS 1999)

– Torfæus på kong Augvalds grunn: (Den nordiske histories fader, Karmøyseminaret 2002)

References:

1. Tormod Torfæus ”Historia rerum Norvegicarum” 1711

2. P. A. Munch: ”Det norske folks Historie” b.1 Christiania, 1852

3. Arnfrid Opedal, ”De glemte skipsgraverne” AmS 1998

4. Odd Nordland: ”Karmsundet og Avaldsnes”, Haugesund museums årshefte, 1950

5. Brian Branston: ”Gods of the North”, 1970

6. Albert A. Joleik ”Soga um Halv”, Oslo 1917.

7. Asgaut Steinnes, ”Utskyld”, i ”Rikssamling og kristendom”, red. A. Holmsen og J. Simonsen

8. Per Hernæs ”Karmøys historie, b. 1, Dreyer, 1997

9. Osebergskipet fra Sørvestlandet. Arkeologi i Nord, 02.03.09 Frans-Arne Stylegar

Other literature

Flateyjarbok, Christiania, 1860

Fornaldersogur Nordurlanda, Gudni Jonsson, 1954

Gøtriks saga, Samspråks forlag AB 1990

Halfs saga ok Halfsrekka, v. A. Le Roy Andrews

Fagerskinna v J. Schreiner, Oslo 1972

Kong Olaf Tryggvesøns saga af Odd Munk, Kbh. 1836

Landnámabók, Kbh.1900,

Fortællinger fra Landnamabok, v. Jon Helgason, 1975

Heimskringla, v Finnur Jonsson, Universitetsforlaget. 1966

Norrøne bokverk, Edda Kvede, Ivar Mortensson-Egnund, 1974

Landnåmsboken, v. K. Schei, Thorleif Dahls kulturbibliotek 1997

L. Skadberg; ”Olavskyrkja og kongsgarden på Avaldsnes” 1950

Skjoldungernes saga , v. D. Erlingson og P. Springberg, Det arnamagnæanske inst.

Gammalnorsk ordbok, Det norske samlaget 1958.

Norsk stadnamnleksikon, Samlaget 1997

Archiv for Skolevæsenets og Oplysnings Utbredelse i Christiansands Stift, Dr. P. Hansen, København 1800

Back