Haakon Haakonsson

Tekst: Marit Synnøve Vea

(Hákon Hákonarson) (1204—1263). King of Noway from 1217 – 1263

«Avaldsnes at Karmøy, 1813″. Painting by J.C. Dahl. The tower that the king built on St Olaf’s Church is very large. Perhaps it should function as a defense tower? (Photo Nasjonal Gallery)

Haakon (Håkon) Haakonsson was born as an illegitimate child of King Haakon Sverresson and Inga of Varteig. He was born in Folkenborg, eastern Norway. His father, the leader of the birkebeiner (birchlegs) faction in the ongoing civil with the bagler, died before Haakon was born. His mother Inga had to carry hot iron (jernbyrd) as a trial by ordeal to prove her son’s right of succession.

Haakon is called the “Prince of the Birchlegs”. The birkebeiner (birchlegs) got their name because their leggings were made of birch bark.

Civil wars

In the period before Haakon’s birth Norway was harried by civil war between the two factions, the “bagler” and the “birkebeiner”. Western Norway and Trøndelag was controlled by the birkebeiner. The bagler was in power in eastern Norway.

Haakon was born in bagler-controlled territory, and his mother feared for his life. A group of birkebeiner warriors fled with the child from eastern Norway in the winter of 1205/06, heading for King Inge in Nidaros. They were stuck by a blizzard, and two of the best birkebeiner skiers, Torstein Skevla and Skjervald Skrukka, carried the baby over the mountain to safety in Trøndelag.

Avaldsnes was a stronghold of the birkebeiner until 1207. Then the bagler faction took the power over Norway as far as the Boknafjord south of Karmøy. Haakon “the Prince of the Birchlegs” were now in their power.

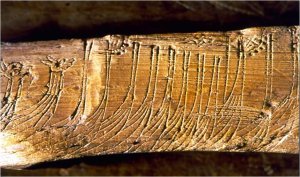

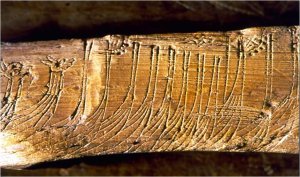

Carving found in Bergen. The carving probably shows Håkon Håkonson’s fleet as Earl Skule of Trøndelag saw it in 1233 when he was summoned to Bergen. Here you see vessels with dragon heads. In the middle you also see ships with gilted banners, a kind of wind vanes, that adorn the prow.

Norwegian realm at the height of its power

Haakon Haakonsson was crowned king of Norway in 1217 when he was only 13 years old. During his reign, the civil war between the bagler and the birkebeiner came to an end. Haakon expanded Norwegian territory to it’s greatest extent. Iceland, Greenland and Finnmark were laid under the Norwegian throne while he was king. Haakon made Bergen the capital of Norway. Inspite the fact that Haakon was an illegitimate child he achieved royal recognition by Pope Innocent, and in 1247 he was crowned by Cardinal William of Sabina according to European custom.

A time of cultural flowering

Under Haakon’s reign literature and the arts flourished and some of the Norse literature was written down. Snorri Sturluson wrote his sagas commissioned by Haakon – but it was also Haakon who got Snorri murdered. Popular European heroic-romantic literature derived from the French and English courts were translated and made available for a Norwegian audience. Haakon also initiated legal reforms which were crucial for the development of justice in Norway.

Strong international contacts

Haakon had a formidable navel fleet reported to count over 300 ships. Due to the strength of his fleet other European rulers wanted to benefit from his friendship. He was highly respected by other European rulers. He was at different points offered the Imperial Crown by the Pope, the Irish High Kingship by a delegation of Irish kings, and the command of the French crusader fleet by the French king Louis IX, an offer Haakon wisely turned down.

Haakon pursued a foreign policy that was active in all directions, and he maintained friendships with both the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, despite their conflict.

In 1258 his daughter Kristina was married to Prince Don Filupus of Castile, but she died four years later after a childless marriage.

Haakon Haakonsson made a peace and trade agreement with Lübeck, which eventually also opened the city of Bergen to the Hanseatic League.

Was King Haakon’s chair placed in the choir of St. Olaf’s church? During the restoration of St. Olaf’s church in 1927, a fresco painting became visible on the north wall of the choir. One of the paintings showed a royal crown, underneath it was a bolt which we believe was the mounting for the king’s chair.

Haakon Haakonsson – the church builder

Haakon Haakonson was constructing several monumental European-style stone buildings, among these were Haakon’s Hall in Bergen which is the largest medieval secular building in Norway

In the saga of Haakon Haakonsson we can read: “At Avaldsnes he (Haakon Haakonson) built a stone church which is the fourth largest country church in Norway.”

Haakon Haakonson started to build his church at Avaldsnes around 1250 as one of his royal chapels. The church was built as an integral part of the royal court. Most of the church was finished before 1280.

When Haakon Haakonsson was to be crowned king, the bishops wanted him to acknowledge Olav the Holy as the supreme king, but Haakon refused. He did, however; dedicate his church at Avaldsnes to Olav the Holy.

When Haakon built the Church of St Olav, Bergen was the capital of Norway. Why, then, did he build his own royal church here at Avaldsnes? This can have both ideological and political reasons:

– Haakon wanted to reinforce his link to the old tradition, and Avaldsnes was an important seat of legendary kings

– It was still important to have control with the shipping traffic passing through the strait Karmsund

– It was an important trading station by the Royal Manor.

Power struggle between the king and the church.

In the time of Haakon Haakonsson there was a power struggle between the king and the church. A papal decree of 1247, nevertheless, states that King Haakon Haakonsson shall have the right to appoint priests for the churches he and his forefathers had built at the three royal courts and also for those churches he would found in the future. In contrast, at all other churches, priests were appointed by the bishops.

The construction of St Olaf’s church at the royal site Avaldsnes, can be seen also as a mark of Haakon’s political “victory” over the bishops and the pope.

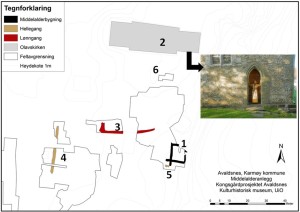

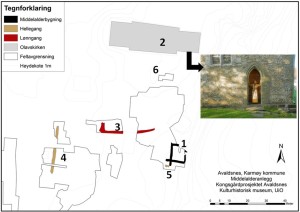

The following are now known to have belonged to the medieval king’s court at Avaldsnes: 1. The ruins of the cellar of the royal hall. 2. The Church of St Olav. 3. An underground passageway. 4. A paved pathway to the west. 5. Parts of a paved pathway south of the ruins. 6. It is likely that an octagonal building, which once stood to the south of the church, also formed part of the king’s court.

Haakon Haakonsson’s Royal Hall?

In July 2012, the Royal Manor Project made an unexpected discovery at Avaldsnes; a Royal Manor built of stone and dating from the Middle Ages was uncovered.

The ruin was found on the plateau just south of St. Olaf’s Church. The location at the edge of the brink, clearly visible against Karmsundet strait, makes us think that this is ruins of the Medieval Royal Hall. The hall is built in Gothic style as part of a larger complex, and it clearly belongs together with the church.

The hall was built sometime between 1250 – 1350, probably by Haakon Haakonsson, who built the Church of St Olaf, or by Haakon V Magnusson, who appointed the Church of St Olaf as one of four collegiate churches in Norway.

This is the fourth Medieval Royal Manor in stone that is found in Norway. The other three are found in Bergen, Oslo and Tønsberg. All these four places were important for Haakon Haakonsson.

The ruin was only partly uncovered. So far, we have found about 50m2 of the lower ground floor. We are not sure how far the ruin reaches into the terrain, but the bedrock rises to the north and part of the upper storey must have been without a lower floor. Because of its thick walls, we can assume that at the upper storey was constructed of stone. The hall may also have had a third floor in wood.

The hall and the church may have been connected – right up to the chancel. For the chancel door opens outwards – a clear sign that there was once a room directly outside it.

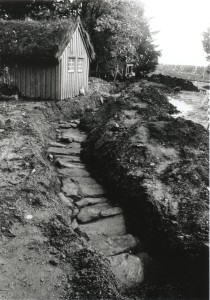

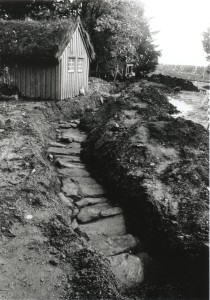

The secret passageway. An escape route for use in times of trouble. In the gravel you see the stone slabs that form the “roof” of the passageway. (Photo AmS)

A paved footpath

In the “Pakterhagen” – the area between the outbuildings to the south and the church to the north – a paved footpath was found which runs alongside the walls of the ruins of the royal hall. We believe that this was the path used by the king when he entered the church. The door to the west was the king’s entrance.

A secret passageway

In 1986, sections of an underground passageway were discovered under the car park by the church. The passageway was probably an escape route in times of trouble. 5.5 m of the passageway run in the direction of the church tower. 30.5 m run towards the site where the royal hall has been found. It looks as if the passageway extends into the ruins of the hall.

After all, Haakon Haakonsson, was born during the Civil War, and he may have felt the need to take precautions. Some believe that the large west tower that the king built on St Olaf’s Church also should function as a defense tower.

The Royal Harbour

We can see that the thrown had an ambitious plan for Avaldsnes in the 13th century. This is reflected in the harbour area.

Archaeological research had revealed that there was a Hanseatic Trading port at Avaldsnes, dating from around 1350 – 1500. While the archaeologists were attempting to define the extent of the Hansa’s harbour, they also came across an older harbour going back to the time of King Sverre and Håkon Håkonsson, i.e. from the end of the 12th century until around 1250.

A tick cultural layer in the see revealed extensive activity in the harbour area around 1170 – 1270. Quantities of animal bones and lots of chopped wood shavings were found in this cultural layer. The shavings can be, either from shipbuilding or ship repair. The findings from the 1200s are of a completely different nature than the findings we have after Hanseatic activity in the same area.

The cultural layer covered an area of about 17.000 square metres, but is probably larger. Many places it continues under the layer with Hanseatic activity.

Haakon dies

In Haakon’s reign Norway lost the sovereignty over some of the islands in the Norwegian skattlondum (tributary countries) in the Irish Sea.

In 1262 The Scottish King Alexander III sponsored Scottish nobles that raided the Hebrides. In 1263 Haakon responded by sending a formidable leiðangr, a war fleet, of at least 120 ships and many men to Scotland.

There were negotiations between Alexander and Haakon, but these were purposely prolonged by the Scots. Finally there was a clash between a smaller Norwegian force and a Scottish division at Largs on the West Coast of Scotland. The battle was fought under a terrible storm. Haakon had to retreat, and he sailed to the Orkneys where he died. The following year his large ship Kristsuden sailed the dead king home to Bergen.

Back