Haakon the good

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

Hákon góði, Hákon Aðalsteinsfóstr (ca 918 – 960) King of Norway from about 935 – 960

Royal Manor at Avaldnes. Probably it was at Avaldsnes and Fitjar Haakon spent most of his time before he was sent to king Athelstan in England. (Foto Gunnar Strøm)

When Harald Fairhair was 70 years old, one of his mistresses, Thora Mostrastong of the Hordakåre clan, bore him a child – Haakon. Haakon was no more than 10 years old when he was sent to England to be brought up by the English king Athelstan. The saga tells of how fond king Athelstan became of Haakon.

Haakon was fostered by the English king Athelstan

According to the saga, Harald Fairhair more or less tricked Athelstan into fostering Haakon so that it would appear that Harald was higher in rank than the English king. The fostering was actually most probably agreed between the two in advance. At this time, Athelstan’s court was a hub of cultural learning where many sons of European princes were taught the arts of statesmanship, military leadership and political strategy.

We have reason to believe that Harald Fairhair and Athelstan were close allies. Archaeological findings from North Rogaland and Sunnhordland point to contact with England at this time and the objects found are of a kind that would have been acquired by peaceful means and not from Viking raids.

The circle marks a possible site for the Royal Manor of Fitjar.

When Haakon was sent to England, Harald Fairhair had become an old man. Perhaps another reason for the arrangement was that Harald wanted to save his youngest son Haakon from falling prey to Eric Bloodaxe, who had been attacking his brothers.

Athelstan equips Haakon with ships and men

When Harald died, Erik Bloodaxe became high king. Erik was not popular with his subjects. Some sagas relate that people in Norway sent a message to Haakon to ask him to return home. Others say that Haakon returned of his own accord. The sagas also recount how Athelstan equipped Haakon with ships and men.

Haakon becomes the king of Norway

Haakon was only 20 years old when he became king of Norway and he reigned for nearly 30 years, nearly as long as his father, Harald Fairhair. Haakon also succeeded in breathing new life into Harald’s project of reunification. Posterity has given him the name of Haakon the Good and he must therefore have had a great deal of political skill and courage.

The core area of Haakon’s territory was originally Harald Hairfair’s old kingdom in Western Norway. Employing the political skills he had learnt in England, Haakon succeeded in reestablishing the alliances that Harald Fairhair had made with the powerful earls of Møre and Lade who accepted him as high king.

Haakon is forced to give up introducing Christianity

In order to reestablish the kingdom of Norway, Haakon had to give up his aim of introducing Christianity. Haakon had converted to Christianity in England and brought both a bishop and perhaps also a priest with him when he returned home to Norway. The saga narrates how he built several churches early on in his reign and found priests to serve in them. It is probable that the royal court at Avaldsnes was one of the places Haakon built a church, even though Olav Tryggvason is traditionally believed to have built the first church here.

However, after a while Haakon had to give up his attempt at christianising the country, not least in order to gain the political support of the earls of Lade, who refused to give up their heathen traditions and Norse gods. When he drank to the heathen gods at Lade, Haakon tried to appease both Christian and heathen rites by making the sign of the cross over the cup that he used to drink to the honour of Odin. But at the yuletide sacrifice at Mære, he had to give in completely; Haakon was required to eat horsemeat and was forbidden to make the sign of the cross when he made toasts to the ancient Norse gods.

Guttorm’s mound at Blood Heights. The name Blood Heights comes from the terrible battle that waged here in 953. Then a Danish/Norwegian fleet led by Eirik Bloodaxe’s sons sailed up the strait of Karmsundet. They landed at Avaldsnes where they fought a bloody battle against their uncle Håkon the Good amongst the Bronze Age mounds on the heights. Local tradition says that Guttorm was buried in Guttorm’s Mound or Prince mound, but this burial mound was 2000 years when Guttorm died here. (Foto Marit S. Vea)

Haakon restores Harald’s kingdom

Harald Fairhair had to build up his kingdom with the help of military power maintained by an all-embracing system whereby farmers were obliged to wine and dine the large band of men who accompanied Harald wherever he went. In order to achieve this, Harald had to expropriate land from the farmers who opposed him and give it to his loyal subjects.

Haakon managed to make peace with the farmers by giving them back their right to the farmlands that Harald Fairhair had taken from them. Within the borders of his kingdom in Western Norway, Haakon could then live in peace, without needing soldiers to protect him against his own people. The military power he needed had to be raised to contend with an enemy from outside: the Danish king and the sons of Eric Bloodaxe.

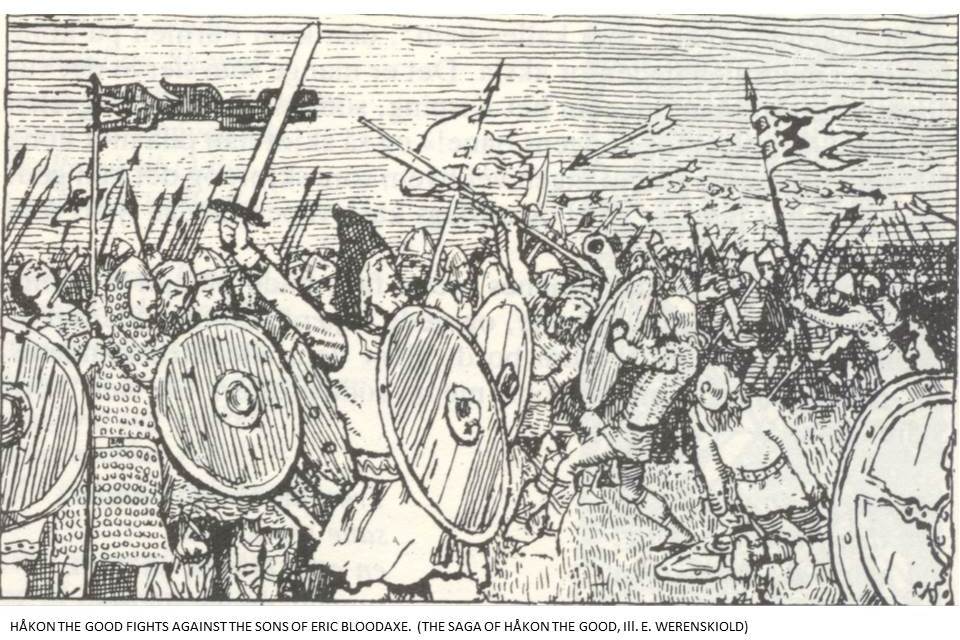

The Battle of Blood Heights

Haakon reigned in peace for a number of years, until the sons of Eric Bloodaxe grew up. With the help of their uncle, Harald Bluetooth, the sons of Eric Bloodaxe came sailing up the strait of Karmsundet with a Danish army in about 953. The two armies waged a bloody battle on a plain near the royal court at Avaldsnes, where burial mounds from the Bronze Age were located. Even though Eric Bloodaxe’s sons had the help of Danish warriors, Haakon the Good managed to win the day.

The battle was by all accounts gruesome. Ágrip tells us that three of Eric Bloodaxe’s sons were slain in this battle. Snorre mentions only Guttorm Erikson. The site of the battle was later given the name of Bloodheights. Snorre relates that when Guttorm fell and his banner vanished into the fray of fighting men, others began to take to their heels and the army disbanded, ran to their ships and rowed away. Haakon and his men pursued them eastwards and both sides sailed as fast as they could until they reached East Agder, where Eric Bloodaxe’s sons then set sail for Denmark, while Haakon and his men returned home.

So says Guthorm Sindre:

The Battle at Blood Heights. (Ill. Christian Krogh. Saga of Haakon the Good)

The king’s voice waked the silent host

Who slept beside the wild sea-coast,

And bade the song of spear and sword

Over the battle plain be heard.

Where heroes’ shields the loudest rang,

Where loudest was the sword-blade’s clang,

By the sea-shore at Kormt Sound,

Hakon felled Guthorm to the ground.

And Guthorm’s brothers too, who know

So skilfully to bend the bow,

The conquering hand must also feel

Of Hakon, god of the bright steel, —

The sun-god, whose bright rays, that dart

Flame-like, are swords that pierce the heart.

Well I remember how the King

Hakon, the battle’s life and spring,

O’er the wide ocean cleared away

Eirik’s brave sons. They durst not stay,

But round their ships’ sides hung their shields

And fled across the blue sea-fields.

(Translation Samual Laing)

After the Battle at Blood Heights, Haakon introduced the institution known as leidang (ON leiðangr ) which was a public levy of free farmers, a form of conscription to organise the Norwegian war and defence fleet

Old photo showing some of the burial mounds on the Reheia, also called Blood Heights because of a battle between Haakon the Good and the sons of Eirik Bloodaxe which took place here in 953.

Haakon organises the leiðangr – the Norwegian war and defence fleet

Haakon and the farmers joined forces to lay the foundations of the leidang, the defence system whereby the country was divided into different regions. In times of strife, those living in each region had to provide a certain number of ships and also equip them with men and weapons. Ancient Norse sources reveal that this Norwegian defence fleet could mobilise over 300 ships when danger threatened. But we do not know whether the full quota of ships was ever mobilised.

In addition, a warning system consisting of hilltop cairns was created and when enemies approached, these cairns were lit one after the other to warn the people so that they could prepare themselves.

The Battle at Rastakalv and the Battle of Fitjar

Two years after the Battle at Bloodheights, the sons of Eric Bloodaxe returned with a Danish army to Frei near Kristiansund, but Haakon succeeded in defeating them once again.

In about 960, Eric Bloodaxe’s sons came north yet again and attacked at Fitjar in Sunnhordland. Haakon managed to drive them away, but was wounded in the shoulder by an arrow.

Haakon dies at Kongshella

The wound to Haakon’s shoulder would not normally have been so serious, but the arrow that pierced him was of a type designed to inflict deep and bloody wounds. Haakon was on his way to the royal court at Alrekstad, but his followers could not stop the bleeding. They went ashore at Kongshella, where Haakon was born about 42 years earlier, and where he finally bled to death by this stone slab.

Haakon was buried like a heathen king with his weapons in a burial mound, but without anything other equipment.

Harald Greycloak

Haraldr Gráfell. King of Norway from about 960 -70

When Harald Greycloak became king of Norway, he accepted his uncle Harald Bluetooth of Denmark as his high king. There were already two kings of Eastern Norway, Gudrød Bjørnson and Trygve Olavson, who paid taxes to Harald Bluetooth. Harald Bluetooth now ruled over a territory stretching from the borders of Grenland in Southeastern Norway and all the way to Møre in the West. Perhaps this was why Harald Bluetooth had the following words hewn into the now famous stone of Jelling, Denmark: “… the Harald who conquered all of Denmark and Norway.”

Some time afterwards, Harald Greycloak killed Sigurd, the earl of Lade. Harald Greycloak – and the king of Denmark – then gained control over most of Norway’s coastal strip, even as far as to Hålogaland in North Norway.

How Harald came to be called Greycloak

King Hakon had generally his seat in Hordaland and Rogaland, and also his brothers; but very often, also, they went to Hardanger. Once, when Harald was on his travels in Hardanger, he met two Icelandic tradesmen who complained that they had not been able to sell the grey sheepskins they had in their ship’s cargo. Harald asked if he could have one of the skins and threw it over his shoulders. After this, there was such a demand for the skins that half of those who wanted to buy one were disappointed – an excellent PR stunt from Harald and the Icelanders! And Harald acquired the name of “Greycloak” as a result.

Harald Greycloak is slain in Denmark

Harald was on his way to help his uncle, Harald Bluetooth, fight against the Franks. He equipped an army and set off southwards. At Hals, in the Limfjord in Denmark, the enemy lay in waiting and Harald was killed. Those of his brothers who survived, then fled the country.

Earl Haakon

Harald Bluetooth let Haakon, earl of Lade, rule Norway on his behalf. Haakon was never called a king, and he paid taxes to the Danish king from about 970 – 995 when Olav Tryggvason came to power in Norway.

Back