Roman Age (0 -400 AD)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

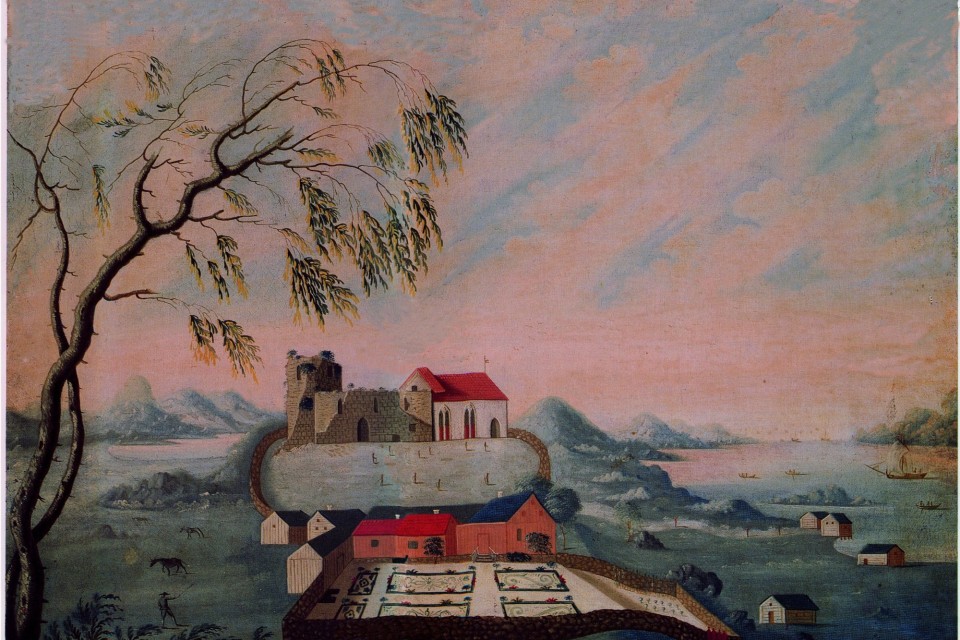

The Flag Mound was situated north of St. Olaf’s Church and stretched well into the current medieval cemetery. Remains of the bottom layer is still preserved outside the stone wall. (Photo KIB Media).

A great many cultural monuments and rich finds from the Late Roman period (ca. 200 – 400 AD) have been discovered in the area of Karmsund and its bordering districts. Something special must have happened, as it appears the population up here in the North had close international contacts at this time. We believe that this is due to the person who was buried in the richest of the graves – the man we call the “Prince of the Flag Mound”. He lived in the 200s, and probably he was the first King who ruled at Avaldsnes, and it would be more correct to call him “The Flag Mound King”.

THE PRINCE IN THE FLAG MOUND (FLAGGHAUGEN)

The Flag Mound lay just north of the medieval church, with a good view over the strait of Karmsundet. The mound was 43 m in diameter and 5 m high. In 1834/35, the secrets of the Flag Mound were uncovered; even though the excavation methods used were extremely sub-standard and much was lost both during and after the excavation, we still have enough information to be able to describe the “Prince of the Flag Mound” in some detail.

The first burial in the Flag Mound took place in the Bronze Age, since then at least 4 secondary burials were placed in the mound. The richest of these was a burial in a stone chamber from the 200s. It is the person in this grave who has subsequently been given the name “Prince of the Flag Mound”. He was laid to rest with more gold than has ever been found in any other grave from the Late Roman period in Norway.

The most splendid object was a massive neckring made of 590 g of pure gold. The Prince of the Flag Mound is the only person in Norway buried with a neckring of gold.

Some objects from the Flag Mound find. The finger ring is the so called “Kolstø ring”, and was found elsewhere at Avaldsnes. (Photo Bergen Museum)

“Written sources reveal that the Franks used bracelets as a symbol of power and that the priests of the Goths wore rings round their necks and arms when carrying out their religious duties. On the Continent, neckrings made of gold were only ever found in the most richly adorned graves, where even the points of arrows were made of silver. Somewhat lower down in the hierarchy were people bearing armrings of gold.“. (From Prof. Bergljot Solberg: “Gravundersøkelser på Vestlandet: Gamle funn – nye tolkninger”, Arkeo 2000, Bergen Museum. 175 år).

ROMAN IMPORTS

It was intended that the Prince of the Flag Mound should not be bored or lack anything he needed for his personal care while in his grave. A board game with 31 pieces of blue and black glass was found, along with a tin-plated bronze mirror, a bronze pair of scales, a complete set of bronze vases and platters, a silver cup, a silver fitting for a drinking horn/signal horn and a bronze wine sieve. These objects are some of the best evidence we have of trade and communication with Roman lands. The same applies to the prince’s weapons.

A SILVER SHIELD BOSS

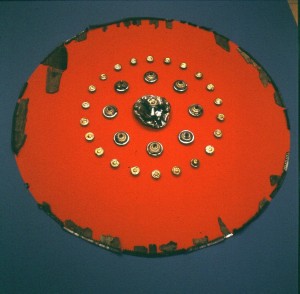

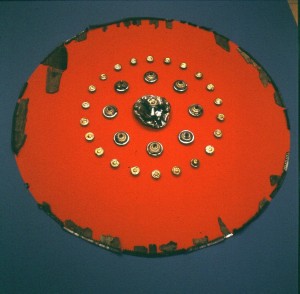

The buried man’s weapons included a lance and spear and also the remains of a shield whose boss was covered with thick layers of silver. The Prince of the Flag Mound is the only person we know of in Norway who was equipped with a shield boss of silver, but this one closely resembles other shield bosses found amongst finds of weapon offerings in Denmark. The shield boss in the Flag Mound is of the same type as one of the magnificent shields from Illerup. The gold plate from the bandoleer and the silver plated fittings on the sheath found in the Flag Mound also have parallels among the stunning finds at Illerup.

WEAPON OFFERINGS AT ILLERUP

The Prince of the Flag Mound is believed to have been associated with a Norwegian-Swedish wave of attacks against Denmark during the period between 200 – 400 AD.

Shield from Illerup. Many of the shields in the Roman period was colored Egyptian blue or vermilion. (Photo Moesgård Museum)

In the marshes at Illerup on Jutland, a prodigious amount of weapon offerings has been found, stemming from an army of 1000 warriors that probably came from Western Norway.

More about the finds in Illerup: Illerup Adal- Archaeology as a Magic Mirror

DOUBLE-EDGED ROMAN SWORD

However, the most striking object in the Flag Mound was a magnificent, double-edged sword. Its grip was adorned with a silver button and the leather-bound sheath was richly decorated with gilded plates of silver. Swords of this kind belonged to the Roman army, so how did the Prince of the Flag Mound come to possess one? Was he one of the Germanic chieftains who fought against the Romans further south in Europe? If so, the sword could be booty taken from a fallen enemy. Or was this man perhaps one of the Germanic chieftains who were in the service of the Romans?

SECONDARY GRAVES IN THE FLAG MOUND

Several other secondary graves were found in the Flag Mound: among these, one not much later than the Prince’s and the other dating from the Age of Migration. These secondary graves also contained imported gold and bronze.

It has recently been confirmed that the scales found in the Flag Mound date from the Viking Era. We can therefore conclude that there was probably also a secondary grave from the Viking Era in the actual Flag Mound. In this case, who was buried there?

LIST OF FINDINGS FROM THE FLAG MOUND

Sword, scabbard and parts of the mirror found in the Flag Mound.

(Photo Bergen Museum)

Secondary grave 1

Gold neckring weighing 590 gr. Unique, no close equivalents. Bears closest resemblance to the only Kolben-style neckring from the Gommern grave in Germany

Gold finger ring weighing 24.075 gr. Five rings of this kind have been discovered in Norway, three of which were found in the counties of North-Rogaland and Sunnhordland

A double-edged sword with a silver button and sheath made of two plates of wood. Possibly a Roman gladius: a one-handed, light-weight stabbing weapon – a standard weapon for soldiers in the Roman army up until ca. 300 AD. The pieces of wood in the sheath were joined together at the edges by small silver fastenings and then covered with leather decorated on the outside with bronze plating and ornamental plates of beaten silver, partially gilded with round ferrules. Similar tin silver ornamentation was found on a sheath fastening at Illerup, Jutland

Shield boss covered with thick sheets of silver. This distinctive boss resembles one of those found at Illerup, Jutland

Bandoleer: one of the beaten gold plates is preserved and a similar one was found on a bandoleer from Illerup, Jutland

31 game pieces of glass. Roman or from a Roman province, perhaps from the Rhinelands in Gaul

Hanging bowl with lion’s head. Provincial Roman. A type of bronze vessel used for hand washing at the Roman table. Unique, no known equivalents. Something similar may be found at Thüringen. Could come from the Danube area or from Italy

Vase (“Hemmorspann”) of bronze with silver inlay. Unique object due to its decoration and small size: provincial Roman: from Gaul, lower Rhinelands. A close counterpart was found at Barnsdorf, Hanover

Bronze sieve. Provincial Roman/Gaul, lower Rhinelands. An important piece of equipment at Roman banquets

Signal horn or drinking horn covered with silver at its opening.

Drinking horn and board game pieces from the Flag mound. (Photo Svein Skare, University Museum of Bergen)

Roman/provincial Roman. Mirrors are extremely rare in the North. A mirror from Hungary is the nearest equivalent

Three small finger rings made of gold

A lance and a spear – both lost. Perhaps a long-shafted lance and a heavy javelin with barbs at the tip

Gold needle, described as “Fine, little gold needle with grooves at the end” – lost

Knife – lost

Arrowhead – lost

Oak plank, spikes and nails

Rope made of bast and animal hair. Plaited?

“Some corals” found during an earlier excavation in 1725. Beads?

Secondary grave 2

Three gold finger rings of “ordinary design”, see point 1, Primary Burial Spann av bronse.

Bronze vase called a “Hemmorspann”

Cremated bones. Lost

One of the finger rings from the primary burial chamber in the Flag Mound. Veight 24,075 g. 5 such finger rings are known in Norway. 3 of them are found in North Rogaland / Southern Hordaland. (Photo: Svein Skare, University Museum of Bergen)

Secondary grave 3

Bronze vessel. Pan from Western Norway

Board game pieces made of bone, unknown quantity

Cloth remains made of coarsely woven wool

Cremated bones

Secondary grave 4.

Scales. Viking Age

Read more: The Flaghaug burials. Frans-Arne H. Stylegar og Håkon Reiersen

THE FLAG MOUND PRINCE’S RESIDENCE

The Royal Manor Project’s excavations in 2011 and 2012 provided us with a picture of the dwelling that the Prince of the Flag Mound and his descendants lived in at Avaldsnes in the Late Roman period.

Hall

At the far end of what is now the car park, south of the church, they built a hall. Buildings of this kind were used for religious and political purposes, not for living in.

The hall went out of use during the last part of the 5th century, i.e. during the early Age of Migration. It was located in a clearly visible position on the rise facing the strait of Karmsundet, halfway between the Celler Mound and the Flag Mound. The constellation of standing stones, including the “Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle”, was probably also erected in the Late Roman Period. Altogether, these three burial mounds and the hall must have been a monumental sight for those sailing through the strait.

In the Viking Age, another hall was constructed on exactly the same site.

Longhouse

The large longhouse built just south of St Olav’s Church also dates from this period. The longhouse had rooms for different functions and it was here that the princes or kings lived during the Late Roman period. This longhouse was rebuilt several times and was in use until well into the Age of Migration, perhaps up until the year 600.

The “kitchen area”

On the plateau further south, a large number of cooking pits were found, many of them dating from the Late Roman period. This was the kings’ “large household kitchen”. One of the cooking pits was so big that meat for at least 100 people could be prepared there at one go – a useful facility when people gathered here for political and religious meetings.

Circular burial site from the late Roman period found at the Kings Height. The circular paving also contained cremated bones from secondary graves and a Viking Age burial. (Photo Marit S. Vea)

The workshop area

South of the church, on the site of the longhouse, a production or workshop area was constructed during the Late Roman period. Forges and ovens associated primarily with metal work were discovered here. This area continued to be a workshop right up until the end of the Viking Age.

CIRCULAR BURIAL SITE AT THE KING’S HEIGHT

During the Late Roman period, somebody was buried in a circular burial site of stones on the hillside called the Kings’ Height. The grave was discovered by the Archaeological Museum in Stavanger in 2005. It had a diameter of between 17 – 20 m. It was not excavated, so we assume that the central burial chamber is still inside the stones.

On the grave’s outer edge to the south, bones from several secondary graves were found. Both cremated and uncremated graves were laid under stone mounds in the Late Roman period. Cremated graves on the edge of a burial area indicate that people were in awe of the person who was buried in the central grave, i.e. the person for whom the grave was originally made.

THE VIRGIN MARY’S SEWING NEEDLE – A PAGAN CULT SITE

The standing stone called the Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle, which stands to the north of St Olav’s Church, is very well known. An ancient saga predicts that Doom’s Day will come when the top of the stone touches the church wall. The stone was originally part of a site comprising several standing stones. Up until now, only three have been fully documented, but it is believed that these stones were a larger counterpart to the “Five Foolish Virgins” at Norheim.

Avaldsnes in the Late Roman Age. The standing stone to the far right is Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle. Digital reconstruction based on archaeological excavations. (Ill. Arkikon)

We assume that the three (or five) standing stones at Avaldsnes formed a pagan cult site or burial place and that they were raised in the Late Roman period. Today, only the Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle still stands in its original position. It is 7.2 metres high, but is believed to have been higher originally.

Tormod Torfæus writes about a standing stone of 15 ell (9.5m) which stood south of St Olav’s Church. The stone cracked when there was a fire at the rectory in 1698. Today, a small part of the stone has been erected south of the church. Earlier written sources tell of a third standing stone which apparently stood a short distance north of Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle. It was described as “colossal”. It was overturned some time before 1841 and lay for a long time in pieces and buried in the cemetery. Nobody knows where its remains lie or exactly where it stood. Remains of a fourth standing stone lie under the pilgrims’ door in the church basement. It may have been necessary to take this stone down when St Olav’s Church was built.

“The Five Foolish Virgins” seen from above. The cluster of standing stones at Avaldsnes might have been a larger counterpart to these standing stones that today can be seen under Karmsund bridge.

THE FIVE FOOLISH VIRGINS

At Norheim, close by Karmsund brigde, there are 5 standing stones known as the “Five Foolish Virgins”. They are situated by the narrowest point of the strait, and were in old times very visible for people who once sailed along the coast. The name comes from the legend about Olav the Holy, but the site is actually a star-shaped burial site dating from the Late Roman period, 300 – 350 AD.

A bronze vessel, wrapped in birch bark, was found in the grave. Inside the vessel were the cremated bones of a middle aged man. Together with the bones were also five bear claws. The bronze vessel indicates that this grave is between 50 -100 years younger than the Flag Mound.

YGGDRASIL, THOR AND STAR-SHAPED STONE MONUMENTS BY THE KARMSUND STRAIT

The two star-shaped stone monuments; one at the site of Avaldsnes royal manor and one at Norheim, are the tallest raised stones in Scandinavia – and the oldest we know in Norway. These two monuments may have connected the site with the sacred tree Yggdrasil and with Thor, the god that protected society from destructive beings.

Remnants of the boathouses at Hop, Ferkingstad with boat slip and a boat landing. (Photo.AmS)

Star-shaped stone formations like this are often seen as a symbolic representation of the world tree Yggdrasil, where fertility cult and sacrifices are important elements. Two skaldic poems, Grimnismal and Gylfaginning says that the god Thor wades across the Karmsund Strait to reach the gods meeting place by the Yggdrasil tree. The mythical motif of the poems may be directly connected to these star-shaped stonesettings, one on either side of the Karmsund Strait.

BOATHOUSES AT FERKINGSTAD

At Hop in Ferkingstad, there are slipways, quays and boathouses big enough for boats up to 30 m long. Hop means “narrow, confined inlet”. The level of the land has risen since the boathouses were in use and today, they stand at 1.5 – 2 m over sea level. The boathouses date from the Roman period. There is also av C-14 dating to the Merovingian period. These boathouses are over 30 m long and 5-6 m wide. The sides are built of large blocks of stone laid on top of one another to make fine, vertical walls.

The ships that were kept here were large enough to cross the Skagerak. We may wonder whether the ships were loaded with goods to sell and bound for the south, or were they full of aggressive warriors like the ones who fell at Illerup?

Rosette fibula. Beautiful costume buckle found in a woman’s grave at Vårå by Avaldsnes. The early 200’s. (Photo AmS)

THE WARRIOR PRINCE WHO BECAME THE KING OF PEACE

There are many theories about the Prince of the Flag Mound: he may have been a leader of an immigrant ethnic group or he may have been an officer in the Roman army who was subsequently given the right to trade with the Romans etc.

There must have been trade between the Roman Empire and Western Norway at this time. Some products from Norway may have been important for equipping the Roman forces, which at their height comprised 650,000 men. The Prince of the Flag Mound may have been given the power to oversee this trade and if so, this would have been a weighty privilege indeed. It would have meant that the Prince had to establish a network of allies, both with other princes on the Continent and with chieftains in neighbouring areas of Norway. Peace was necessary to secure the trade along the coast. The Prince of war became the King of peace.

A grave of equally high status as that of the Flag Mound has been discovered in Bulgaria. The Flag Mound grave is also similar in many ways to a prince’s grave in Gommern in the Rhinelands.

Beakers found in a tomb on the island of Feøy. Late Roman period. (Photo AmS)

If we compare archaeological material with information from Roman sources about the movements of the two Germanic tribes the “Rygers” and “Horders” at this time, interesting questions arise about a subject on which little research has been done. The rich finds in the Flag Mound must be due to Avaldsnes’ central location on the strait. Avaldsnes was located at the natural intersection of the shipping fairway from the North and the ocean-going traffic to Jutland and ports further west on the Continent.

ROMAN CULTURAL HUB AT AVALDSNES

Throughout the Karmsund area, there are rich remains from the Late Roman period, including the Flag Mound. In the words of prof. Haakon Shetelig:

“I wish in particular to mention one centre for foreign trade during the first centuries AD: Avaldsnes at Karmøy. […] Roman imported goods are found both in the northern and southern parts of Western Norway, but there is no other place with such dense concentrations of findings than at Karmsund. Avaldsnes […] can almost be regarded as a hub for all cultural dissemination along the west coast of Norway.”

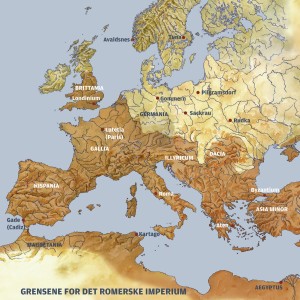

ETHNIC MIGRATIONS DURING THE ROMAN AGE

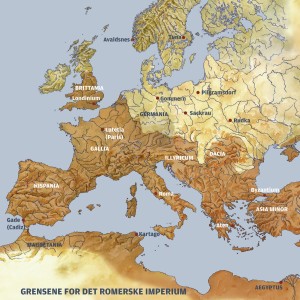

The Age of the Romans, from the birth of Christ to ca. 400 AD, was marked by major upheavals. The Roman Empire reached the height of its power and geographical size before its decline and division in year 395 into an eastern and western empire. Germanic tribes wandered from place to place in Europe and fought both with and against the Romans.

Borders of the prevalence of the Roman Empire. (Ill Day Frognes)

Around the year 100, the Roman historian Tacitus described many of these tribes. For example, he writes about the Rygers, the ethnic group from which the name of the Norwegian county of Rogaland is derived.

Last update November 2022

Back