Migration Period (400 – 550 AD)

Text: Marit Synnøve Vea

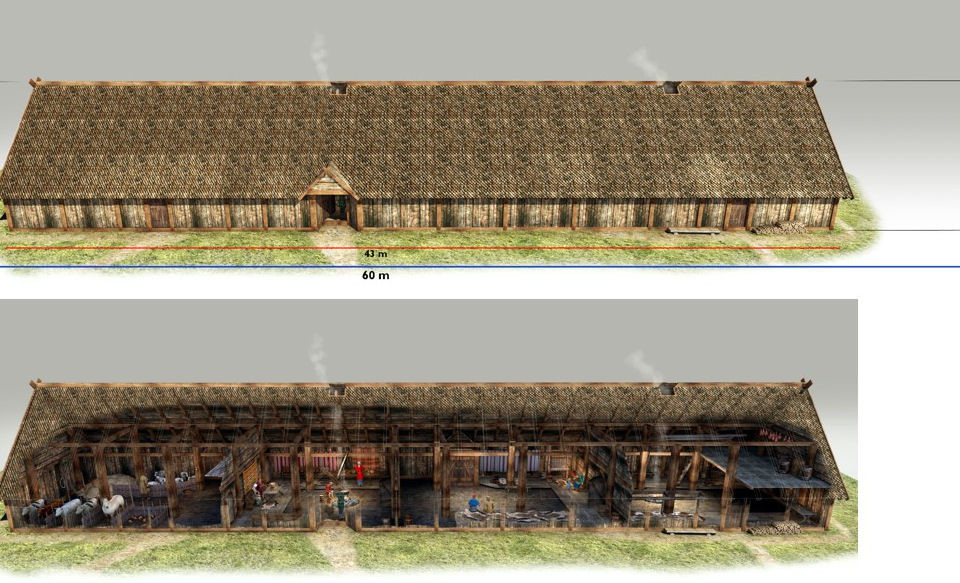

The longhouse found just south of the church was 8 m wide and perhaps as much as 70 m long. (Photo Ørjan Iversen)

Both sagas of the national kings and the heroic sagas tell the story of the legendary “migration king” Augvald who gave his name to Avaldsnes. After winning a number of battles at sea, he drove out the earlier rulers and settled on the headland (= “nes” in Norwegian) by the strait Karmsund which was later known as “The Nes of Augvald”, Avaldsnes.

LONGHOUSE FROM THE LATE ROMAN/MIGRATION PERIOD

In 2012, the Royal Manor Project discovered a large longhouse in the area just south of St Olaf’s Church. This was the dwelling house of those who ruled here during the Late Roman and Migration Period. Perhaps the chieftains whom Augvald conquered also lived here? And perhaps Augvald himself lived in this building.

The longhouse had internal walls which divided it into rooms used for different purposes. The holes from the construction posts or stanchions reveal that the longhouse had been rebuilt several times and we believe that it was in use for several centuries during the period 300-600 AD.

The longhouse must have been of great length, perhaps as long as 70 metres. The archaeologists uncovered about 23m of the house on site, probably the middle section of the original longhouse, and there was no indication that they were anywhere near the last pair of posts, either to the south or north. Neither did they discover any longitudinal curvature, as is normally found in houses from this period. This would indicate that the house was originally very long indeed.

The width of the house was about 8m and the distance between the posts supporting the roof was about 4m, further indications that this was a very long house. The roof supporting posts had a diameter of between 30-74cm and were very sturdy – a sign that the house must also have been high-ceilinged.

Bucket-shaped pot from Avaldsnes. Pots of this shape were used for rites. Nearly all such pots from Rogaland contain chrome from a volcanic type of rock that is very rare, but we find it in Helganes (= Holy Headland) at Avaldsnes. (Photo AmS)

BUCKET-SHAPED CLAY POT USED FOR RITUALS?

During the 2012 excavation, a rather modest-looking, bucket-shaped pot was discovered, dating from late 4th century, i.e. immediately before the advent of the Migration Period – an era when bucket-shaped pots abounded. As time went on, these pots were also extremely beautifully decorated. The pot found at Avaldsnes was only simply decorated, but the clay it was made of was unusual.

Nearly all bucket-shaped pots from Rogaland contain chrome from a volcanic type of rock that is only found on Karmøy in this region, more precisely at Syre and on Helganes (= Holy Headland). This volcanic rock has no practical function, so why did the local people from all over Rogaland fetch a volcanic rock from Karmøy and mix it with the clay they used to make the pot? Pots of this shape were used for rites; was it the rock itself or the place the rock came from that the people of Migration Period believed was sacred?

HILL FORTS

Many hill forts built in rural areas for defence purposes during times of strife have been found in Norway. Hill forts were erected in the Roman period, but we believe that the majority were constructed during the Migration Period. They may have still been in use a long time after this. Hill forts were defensive fortifications. On Karmøy, only three hill forts of this kind have been discovered, perhaps because people here did not feel particularly threatened?

Bårholmen sentry post for the royal court. ( bår from borg, meaning fortress) (Photo Marit S. Vea)

Storaborg hill fort is situated on the southern tip of Karmøy at Skudenes Harbour, Steinsfjellet hill fort lies in the centre of Karmøy, near Åkrehamn, and Bårholmen lies hidden between spruce trees on an islet at Visnesvågen, west of the royal court at Avaldsnes. The latter is too small to be a traditional hill fort. Rather, we believe it was a kind of sentry post for the royal court at Avaldsnes, in case enemies came sailing in by sea from the west.

KING AUGVALD – OGVALDR

Avaldsnes plays a central role in the history of Western Norway, as it is told in the heroic sagas and poems. In these stories, we come across legendary kings and heroes living during the centuries before the Viking Age. One of these is Augvald, the king of the Migration Period, after whom Avaldsnes is said to be named.

The Old Norse name for Augvald was Ogvaldr. His name may mean ” “he who is held in awe” while others include “the ruler of the coast” (from “ogð”, meaning “stretch of coast”). In some sources, the term for “king” is “vordr véstalls” or “ves valdr“, meaning “the protector and ruler of the sacred place.” (Britt-Mari Näsström: Beliefs and sacrifices in pre-Christian Scandinavia, 2001)

The hill King’s Height has received its name because king Augvald supposedly was buried here. In 2005, the archaeologists found a burial mound from the Migration Period in the northern end. (Photo Oliver Iversen)

Augvald is believed to have lived around the year 600 AD and he is described as “the descendant of the gods and the ancestor of the kings”. The ancient genealogies tell us that Augvald could trace his family line back to the very first Jotun giant called Fornjot or Ymir, the first being created together with the first cow Audhumla, when fire and ice came together to make the world. (See Augvald)

ODIN AND AUGVALD

Snorre Sturlason relates that Odin himself came to Avaldsnes and told Olav Tryggvason the story about King Augvald and the cow he worshipped. According to Snorre, both Augvald and the sacred cow were buried at Avaldsnes and another old document written by Odd Munk explains that Olav Tryggvason dug two of the burial mounds at Avaldsnes. In one of the mounds, he found King Augvald’s bones and in the other, bones from Augvald’s divine cow.

KING FERKING AND KING AUGVALD

An old legend from this area recounts the story of how King Augvald was killed in a battle against King Ferking from Ferkingstad. Unlike King Augvald, Ferking is not mentioned in written historical sources, but the legend has been kept alive on Karmøy right up until the present day and King Ferking has been linked to the ruins of a building called the “King’s Fortress” and two large boathouses at Ferkingstad.

Slipways, boat landing places and boathouses large enough to accommodate 30m long boats, at Hop, Ferkingstad. (Photo AmS)

FERKINGSTAD

Ferkingstad (from “farþegn”, meaning “travelling lord”) lies on the furthest tip of the west side of Karmøy, facing the open sea. Here there are a grave, a boat ramp, a boat slipway, a track and remains of tree boathouses. One boathouse is 33 m long and 8 m wide in, one is 30 m long and almost 6 m wide. The sides of these boathouses are built of large blocks of stone laid on top of one another to make fine, vertical walls. Traces of the third boathouse can barely be seen under the other two.

The boathouse complex has not been excavated, but exploratory tests carried out in 1960 give a dating to Roman times (1-400 AD) and the Merovingian period (550-800 AD). The oldest dating must be from the boathouse which lies underneath the other two.

The level of the land has risen since the boathouses were in use and today, they stand at 1.5 – 2 m over sea level. The water here is named Hoptjønn which is derived from the Old Norse word “hop”, meaning a “narrow, confined inlet”.

The boathouses lie in a sheltered harbour, tucked away behind outcrops of rock which protect them against the ravages of the sea. From here, ships could be sent out to catch tax-evaders who sailed past the outside of Karmøy in an attempt to avoid paying tax in the strait of Karmsundet.

More pictures of the boathouse complex here.

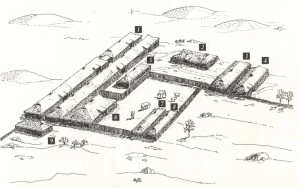

THE KING’S FORTRESS

At Ferkingstad there were, in addition to burial mounds and standing stones, also the remains of large buildings which the local people call “The King’s Fortress”

THE KING’S FORTRESS AT FERKINGSTAD

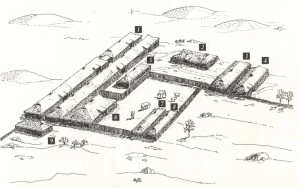

Reconstruction after J. Neumann’s sketch. The total area for the site was 3,300km2.

1. banquet halls ca. 60 metres long, 2. storehouse, 3. sauna, 4. barn, 5 house for food making, 6 farmhouse, 7. farmhouse, 8. farmhouse, 9.farmhouse. (Ill. Hult/Svendsen)

Findings of pottery have allowed us to date the remains of the building from the Migration Period. In 1837, Bishop Neumann was on Karmøy to register this historical monument and he describes the ruins as follows: “This site exceeds in magnificence everything else that has been handed down to us from the power and glory of ancient heathen times, to the degree that they without doubt are unique and cannot be compared with any other monuments (…).”

Bishop Neumann linked the remains of this building to King Ferking’s fortress and the old, local legend about King Ferking and King Augvald. When J. Neumann visited Ferkingstad, he drew a basic sketch of the site at Hedlabakkane.

THE KING’S FORTRESS – A VILLAGE FROM THE MIGRATION PERIOD?

In 1923, Jan Petersen carried out a few trial excavations on the site of the King’s Fortress. He found pottery dating back to the Migration Period. Petersen concluded that the site was the remains of a village from this era.

The remains of the building and all the standing stones at Ferkingstad were slowly but surely removed and used to build stone walls and fences. But on a fine summer’s day, yellow stripes in the grass reveal that there are still remains lying in the ground.

FERKING – TITLE OR NAME?

We are not sure whether Ferking was the name of one special chieftain or the title or several chieftains who constructed the buildings and boathouses at Ferkingstad.

One of the “Shield Maidens” at Stava field. (Photo Marit S. Vea)

SHIELD MAIDENS – VALKYRIES

According to the old legend from this area, Augvald had two daughters who were shield maidens and fought with their father in all the battles. Shield maidens were female warriors who could “ride the wind over land and sea”. They could also be goddesses of fate, related to the Norns. Odin sent shield maidens to the battlefield to choose which of the fallen should be taken to Valhalla. They were therefore called “Odin’s maidens”.

The legend relates that Augvald’s shield maidens were buried at Stavasletta. Here, there are still two standing stones which are called The Shield Maidens. These two stones were originally part of a star-shaped burial monument which resembles the burial site named “The Five Foolish Virgins” at Norheim by the strait Karmsund. At the burial site at Stavasletta, there are now only two stones left, but as late as in 1965, 5 standing stones were registered here. Two had fallen down and one had been incorporated into a stone fence.

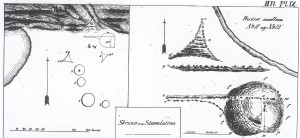

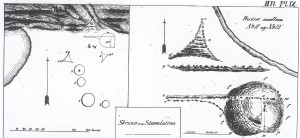

Bishop Neumann’s sketch of the burial site at the field of Stava from 1837.

THE BURIAL SITE AT STAVA

The “Shield Maidens” were part of an extensive burial site at Stava. When Bishop Neumann was registering cultural monuments on Karmøy in 1837, the site was still partly intact.

The present-day name of the sea on the left side of the sketch is Båsvika (meaning “boat inlet”). The burial site that the “Shield Maidens” belonged to is in the top right-hand corner. The sketch shows that the shapes of the graves on the site were unusually varied. Based on findings from the area, we believe that the age of the graves spans from the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period.

More pictures of the burial site here.

BOATHOUSE AT STAVA FIELD

Immediately northeast of the burial site lies the site of a partly demolished boathouse that has not attracted much attention. It lies about 50 metres up from the Båsvika inlet. Its walls are almost flush with the surrounding terrain.

Remains of the boathouse at Stava field. In 1979 the boathouse was measured to be 35m long, and 10m wide. (Photo Marit Synnøve Vea)

The long south wall is the best preserved; the other walls consist of earthworks with partially visible stones.

In 1979, the site of the building was 35m long from east to west and 10m wide from north to south. A road runs over it, and the building may have been even longer.

RELIEF BUCKLE FROM SYRE

In 1964, a large and beautifully engraved costume buckle was found at Syre near Skudenes Harbour. It was buried in the ground together with two sets of clasps.

The buckle and the clasps date from the 7th century, a time of transition between the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period. Perhaps the buckle was hidden away because it was a time of trouble. What happened to the owner, who never came to fetch the buckle?

Relief buckles of this sort have been found on both sides of the North Sea, both in Norway and in the British Isles – and in such quantities that it would appear that people on both sides of the sea were in direct contact with one another a long time before the Viking raids began.

Relief buckle from Syre. The ornamentation shows animals that twist themselves into each other. (Photo AmS)

CONTACT ACROSS THE NORTH SEA LONG BEFORE THE VIKING AGE

One particular historic event, the attack on the Lindisfarne Monastery in 793, is believed to be the first known Viking raid. Nevertheless, Bishop Alcuin chides the people in Northumbria for imitating the pagan attackers’ mode of dress and hairstyle. Is this not proof that the people here knew the attackers already, but perhaps as seamen or merchants?

There are signs of contact over the North Sea long before the Age of the Vikings. In East England there are archaeological clues showing links to the West of Norway as far back as 400 AD. So when did the direct contact with the Western Isles of Scotland, Ireland and England actually begin?

We know that people living in West Norway had been crossing the Skagerrak in large rowing boats for a very long time, but was it necessary for them to have sailing ships in order to dare to undertake the journey over the North Sea?

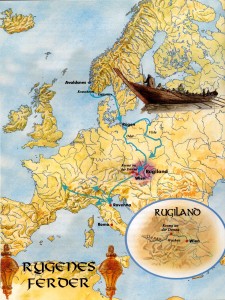

THE MIGRATION OF THE GERMANIC “RYGER” TRIBE?

The Migration Period is characterised by major upheavals – the Roman Empire collapses and Germanic tribes migrated from place to place in Europe.

Some believe that certain of these Germanic-speaking tribes emigrated from Scandinavia; several ethnic groups had myths telling of their origins from “Scandza”, a land to the north.

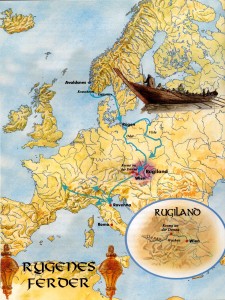

THE MIGRATIONS OF THE RYGER ON THE CONTINENT

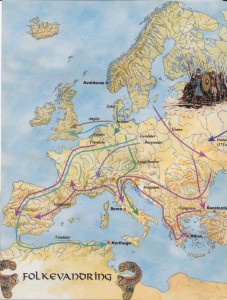

“Rygers” and “Horders” are two Germanic tribes who supposedly have given name to the counties of Rogaland and Hordaland. They have been identified with the “rugiers” (rugii) and “haruders” (harudes) we know about from the migrations on the Continent. (Map after Torgrim Titlestad/DagFrognes)

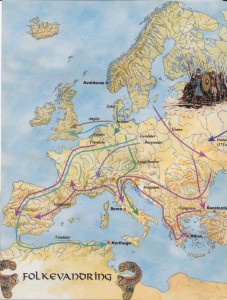

MIGRATION OF THE GERMANIC TRIBES.

Map after Torgrim Titlestad/Dag Frognes

Some of the archaeological findings in West Norway dating from this time appear to indicate that something new had happened. It may also be that new groups emigrated to Norway from Europe. “Rygers” and “Horders” are two Germanic tribes whom the present-day counties of Rogaland and Hordaland are believed to be named after.

“Rygers” and “Horders” have been identified with the “rugiers” and “haruders” we know about from the migrations on the Continent and whom the Roman historian Tacitus (100 AD) calls “rugii” and “harudes”.

Last update November 2022

Back